Metamorphoses by Ovid. I, 253 – 434: The Flood.

I, 253 – 434

- Iamque erat in tōtās sparsūrus fulmina terrās;

sed timuit, nē forte sacer tot ab ignibus aether

- conciperet flammās longusque ardesceret axis.

Esse quoque in fātīs reminiscitur adfore tempus,

quō mare, quō tellus correptaque rēgia caelī

ardeat et mundī mōlēs operōsa labōret.

Tēla repōnuntur manibus fabricāta Cyclōpum:

- poena placet diversa, genus mortāle sub undīs

perdere et ex omnī nimbōs dēmittere caelō.

Prōtinus Aeoliīs Aquilōnem claudit in antrīs

et quaecumque fugant inductās flāmina nūbēs,

ēmittitque Notum: madidīs Notus ēvolat ālīs

- terribilem piceā tectus cālīgine vultum:

barba gravis nimbīs, cānīs fluit unda capillīs,

fronte sedent nebulae, rōrant pennaeque sinusque;

utque manū lātē pendentia nūbila pressit,

fit fragor: hinc densī funduntur ab aethere nimbī.

- Nuntia Iūnōnis variōs indūta colōrēs

concipit Īris aquās alimentaque nūbibus adfert:

sternuntur segetēs et dēplōrāta colōnīs

vōta iacent longīque perit labor inritus annī.

Nec caelō contenta suō est Iovis ira, sed illum

275 caeruleus frāter iuvat auxiliāribus undīs.

Convocat hīc amnēs, quī postquam tecta tyrannī

intrāvēre suī, ‘nōn est hortāmine longō

nunc’ ait ‘ūtendum: vīrēs effundite vestrās;

sic opus est. Aperīte domōs ac mōle remōtā

280 flūminibus vestrīs tōtās inmittite habēnās.’

iusserat: hī redeunt ac fontibus ōra relaxant

et dēfrēnātō volvuntur in aequora cursu.

Ipse tridente suō terram percussit, at illa

intremuit mōtūque viās patefēcit aquārum.

285 Exspatiāta ruunt per apērtōs flūmina cāmpōs

cumque satīs arbusta simul pecudesque virōsque

tectaque cumque suīs rapiunt penetrālia sacrīs.

Siqua domus mansit potuitque resistere tantō

indeiecta malō, culmen tamen altior hūius

290 unda tegit, pressaeque latent sub gurgite turrēs;

iamque mare et tellus nullum discrimen habēbant:

omnia pontus erant, deerant quoque lītora pontō.

Occupat hīc collem, cumbā sedet alter adunca

et dūcit rēmōs illīc, ubi nūper arārat;

295 ille suprā segetēs aut mersae culmina villae

nāvigat, hic summā piscem dēprendit in ulmō;

fīgitur in viridī, sī fors tulit, ancora prātō,

aut subiecta terunt curvae vīnēta carīnae,

et, modo quā gracilēs grāmen carpsēre capellae,

300 nunc ibi dēformēs pōnunt sua corpora phōcae.

Mīrantur sub aquā lūcōs urbēsque domōsque

Nēreidēs, silvasque tenent delphīnes et altīs

incursant ramīs agitātaque rōbora pulsant.

Nat lupus inter ovēs, fulvōs vehit unda leōnes

305 unda vehit tigrēs, nec vīrēs fulminis āprō,

crura nec ablātō prōsunt velōcia cervō,

quaesītisque diū terrīs, ubi sistere possit,

in mare lassatīs volucrīs vaga dēcidit ālis.

Obruerat tumulōs inmensa licēntia pontī,

310 pulsābantque novī montāna cacūmina fluctūs.

Maxima pars undā rapitur: quibus unda pepercit,

illōs longa domant īnōpī ieiūnia victū.

Sēparat Aoniōs Oetaeīs Phōcis ab ārvīs,

terra ferax, dum terra fuit, sed tempore in illō

315 pars maris et lātus subitārum campus aquārum;

mons ibi verticibus petit arduus astra duobus,

nōmine Parnāsus, superantque cacūmina nūbēs:

hīc ubi Deucalion (nam cētera texerat aequor)

cum consorte torī parvā rate vectus adhaesit,

320 Corycidās nymphās et nūmina montis adōrant

fātidicamque Themin, quae tunc oracla tenēbat:

nōn illō melior quisquam nec amāntior aequī

vīr fuit aut illā metuentior ulla deōrum.

Iuppiter ut liquidis stagnāre palūdibus orbem

325 et superesse virum dē tot modo mīlibus ūnum

et superesse videt dē tot modo mīlibus ūnam,

innocuōs ambō, cultōrēs nūminis ambō,

nūbila disiēcit nimbīsque aquilōne remōtīs

et caelō terrās ostendit et aethera terrīs.

330 Nec maris īra manet, positōque tricuspide tēlō

mulcet aquās rector pelagī suprāque profundum

exstantem atque umerōs innātō mūrice tectum

caeruleum Tritōna vocat conchaeque sonantī

inspirāre iubet fluctusque et flūmina signō

335 iam revocāre datō: cava būcina sūmitur illī,

tortilis, in lātum quae tūrbine crescit ab īmo,

būcina quae mediō concēpit ubi āëra pontō,

lītora vōce replet sub utrōque iacentia Phoebo.

Tunc quoque, ut ōra Deī madidā rōrantia barbā

340 contigit et cecinit iussōs inflata receptūs,

omnibus audīta est tellūris et aequoris undīs

et, quibus est undīs audīta, coercuit omnēs.

Iam mare lītus habet, plenōs capit alveus amnēs,

flūmina subsīdunt collesque exīre videntur,

345 surgit humus, crescent loca dēcrescentibus undīs,

postque diem longam nūdāta cacūmina silvae

ostendunt līmumque tenent in fronde relictum.

Redditus orbis erat; quem postquam vidit inanem

et dēsōlātās agere alta silentia terrae.

350 Deucalion lacrimīs ita Pyrrham adfātur obortīs:

Ō soror, ō coniunx, ō fēmina sōla superstes,

quam commune mihī genus et patruēlis orīgo

deinde torus iunxit, nunc ipsa perīcula iungunt,

terrārum, quascumque vident occāsus et ortus,

355 nos duo turba sumus: possedit cētera pontus.

Haec quoque adhuc vītae non est fidūcia nostrae

certa satis; terrent etiam nunc nūbila mentem.

Quis tibi, sī sine mē fātīs ērepta fuisses,

nunc animus, miseranda, foret? Quō sōla timōrem

360 ferre modo posses? Quō consolante dolēres?

Namque ego, crede mihī, sī tē quoque pontus habēret,

tē sequerer, coniunx, et mē quoque pontus haberet.

Ō utinam possim populōs reparāre paternīs

artibus atque animās formātae infundere terrae!

365 nunc genus in nōbis restat mortāle duōbus

(sic vīsum superīs) hominumque exempla manēmus.”

Dixerat, et flēbant; placuit caeleste precāri

numen et auxilium per sacrās quaerere sortēs.

Nulla mora est: adeunt pariter Cēphīsidas undās,

370 ut nondum liquidās, sic iam vada nōta secantēs.

Inde ubi lībātōs inrōrāvēre liquōrēs

vestibus et capiti, flectunt vestigia sanctae

ad dēlubra deae, quōrum fastīgia turpi

pallēbant muscō stabantque sine ignibus ārae.

375 Ut templī tetigēre gradūs, procumbit uterque

prōnus humī gelidōque pavens dedit oscula saxō

atque ita “sī precibus” dixērunt “nūmina iustīs

victa remollescunt, sī flectitur īra deōrum,

dic, Themi, quā generis damnum reparābile nostri

380 arte sit, et mersīs fer opem, mītissima, rēbus.”

Mota Dea est sortemque dedit: “discēdite templō

et velāte caput cintāsque resolvite vestēs

ossaque post tergum magnae iactāte parentis.”

Obstipuēre diū, rumpitque silentia voce

385 Pyrrha prior, iussisque Deae pārēre recūsat,

detque sibī veniam, pavidō rogat ōre pavetque

laedere iactatīs maternās ossibus umbrās.

Intereā repetunt caecīs obscūra latebrīs

verba datae sortis sēcum inter sēque volūtant.

390 Inde Prōmetides placidīs Epimēthida dictīs

mulcet et “aut fallax” ait “est sollertia nōbis,

aut (pia sunt nullumque nefās ōrācula suādent)

magna parens terra est: lapidēs in corpore terrae

ossa reor dīcī: iacere hōs post terga iubemur.”

395 Coniugis auguriō quamquam Titānia mōta est,

spēs tamen in dubiō est: adeō celestibus ambo

diffīdunt monitīs, sed quid temptāre nocēbit?

Discendunt vēlantque caput tunicāsque recingunt

et iussōs lapidēs sua post vestīgia mittunt.

400 Saxa (quis hoc credat, nīsī sit prō teste vetustās?)

pōnere dūritiem coepēre suumque rigōrem

mollīrīque morā mollītaque dūcere formam.

Mox ubi crēvērunt nātūraque mītior illīs

contigit, ut quaedam, sic non manifesta vidērī

405 forma potest hominis, sēd, uti dē marmore coepta,

non exacta satis rudibusque simillima signīs.

Quae tamen ex illīs aliquō pars ūmida sūcō

et terrēna fuit, versa est in corporis usum;

quod solidum est flectīque nequit, mutātur in ossa;

410 quae modo vēna fuit, sub eōdem nōmine mansit;

inque brevī spatiō superōrum nūmine saxa

missa virī manibus faciem traxēre virōrum,

et dē fēmineō reparāta est fēmina iactū.

Inde genus dūrum sumus experensque labōrum

415 et documenta damus, quā simus orīgine nātī.

Cētera dīversīs tellūs animālia formīs

sponte suā peperit, postquam vetus umor ab igne

percaluit sōlis caenumque ūdaeque palūdes

intumuēre aestū fēcundaque sēmina rērum

420 vīvācī nutrīta solō ceu matris in alvō

crēvērunt faciemque aliquam cēpēre morando.

Sīc ubi dēseruit madidōs septemfluus agrōs

Nīlus et antiquō sua flūmina reddidit alveō

aetheriōque recens exarsit sīdere līmus,

425 plūrima cultorēs versīs animalia glaebis

inveniunt et in hīs quaedam inperfecta suīsque

trunca vident numeris, et eōdem in corpore saepe

altera pars vīvit, rudis est pars altera tellūs.

430 Quippe ubi temperiem sumpsēre umorque calorque,

concipiunt, et ab hīs oriuntur cuncta duōbus,

cumque sit ignis aquae pugnax, vapor hūmidus omnēs

rēs creat, et discors concōrdia fetibus apta est.

Translation

Jupiter was already about to cast his lightning on all lands, when he feared that the sacred ether too could burn for the enormous flames and that the axis of the world could continue to burn for a long time. He also remembered the prophecy that there would be a time when the sea and the earth and the celestial kingdom would be completely destroyed by flames and the whole cosmos, in trouble, would suffer. The darts made by the hands of the Cyclops were then put away and Jupiter decided a different punishment: the deadly kind would perish under the waves: it was so that stormy clouds lowered from the sky.

So he immediately locked up in the Aeolian caves the Kite and all the winds that disperse the clouds and instead freed the Noto: he flew with his wings soaked and with the frightening face tinged with black caligin as pitch: The beard, heavy with the massive clouds, flowed like a wave of white hair, on the forehead dwelt the mists, while the feathers and the folds of the clothes dripped with water; when with the extended hand squeezed the heavy clouds, a thunder was generated: from which the thick storms spread from the ether.

Iris, the messenger of Juno, dressed in many colours, collected water and fed the clouds: the fields were destroyed and laid desolate, mourned by the peasants, and so the effort of a long year of work was needlessly lost.

Nor was Jupiter’s wrath limited to the sky, but his cerulean brother supported him with the help of the waves. So Neptune summoned the streams, and as soon as they reached the homes of their Lord, he said, “There is no need for a complicated command: you have to unleash your forces. He ordered, “Open your homes and feed your rivers with an immense amount of loose water”. The streams returned and released water to the springs and unbridledly poured into the sea. Neptune struck the earth with his trident and that trembled, leaving the ways open to the movement of the waters. The rivers, scattered in every direction, flowed over the vast fields dragging in some way with them trees, cattle, people, houses and temples with their sacred furnishings. The wave then submerged what had not yet been destroyed yet, even the highest peaks, and the towers were pressed by the force of the water disappeared between the waves. It was no longer possible to distinguish the land from the sea, because everything was sea and the coast was nowhere to be seen.

Somebody tried to escape on a hill, sombody else sat on a curved boat and rowing went where he had just ploughed, another sailed over the fields just sown or over the roof of his house now submerged, another picked up a fish from the top of an elm; it happened by chance that someone threw his anchor on a green meadow or that the curved hulls rubbed against the submerged vineyards, and where the pretty goats were grazing shortly before, now the seals lay down their deformed bodies. The Nereids were amazed to see underwater woods, cities and houses, the dolphins occupied the woods and hit the highest branches, shaking them brightly with force. The wolf swam among the sheep, and the wave carried away the tawny lions, and also the tigers; neither the lightning forces helped the wild boar, nor the fast legs helped the deer dragged away by the current, and the birds let themselves fall into the waves, now exhausted for having long in vain searched for a piece of land to rest on. The immense expanse of seawater flooded the heights and new waves fell on the peaks of the mountains. Most of the living creatures died in the waves: those spared were killed by a long fast for lack of food.

The Phocis, which when it was not yet submerged was a fertile land, separates Aonia from the region of Eta, and was now part of the vast sea. There, a steep mountain called Parnassus tends to the stars with two peaks, which exceed the clouds: as soon as Deucalion with his wife, carried by a small raft, anchored there with a small cord (in fact the sea covered everything else), he performed a ritual of worship for the Koricite nymphs, for the Gods of the mountains and for the prophetic goddess Themis, who then used to dispense oracles: there was no one better than him or juster, nor anyone more respectful of the Gods than her.

Jupiter, when he saw that the world was stagnant with swamps and that only one man among many thousands and one woman among many thousands had survived, both honest, both worshipers of the Gods, scattered the clouds and after recalling the storms, with the wind Aquilon, made the earths visible to the sky and the sky to the earths. The wrath of the sea ended, and after deposing the trident the king of the sea calmed the waters and summoned to the surface from the depths the cerulean Triton with his shoulders covered with shells grown on him and ordered him to blow in the bugle and to recall the waves and rivers with the agreed signal: he grabbed the concave and twisted bugle. It grew from the bottom of the sea like a great vortex and when it resounded in the middle of the sea, with its sound it filled the coasts that were in every part of the world. And also that time, when the mouth of the God, moistened by the soaked beard, took it, and when the trumpet received the blow and sounded the orders to return, it was heard by all the waves on earth, inmediately placating them. The coast was already reappearing by the sea, the streams were containing the masses of water, the rivers were retreating, the hills were emerging, the ground appeared, the mainland extended as the seas narrowed, and after a long day the woods showed the bare tops of the trees, holding back the mud with the foliage.

The earth had been saved, but Deucalion saw that it was empty and that absolute silence reigned over the wastelands, and then turned to Pyrrhas in tears:

“Sister, bride, only survivor among women, that you were united to me by the same people, by the same paternal origins, and then by marriage, now instead are the dangers that unite us, because throughout the land, from east to west, there are only the two of us, because all the others have disappeared into the sea. I don’t even feel safe for our lives because I still have in me the terror aroused by the storm. What would have happened to you if you had saved yourself without me, how would you have been, you unlucky woman? How could you have faced fear, completely alone? How would you have consoled your pain? In fact, believe me, if the sea had taken you too, I would have followed you, my wife, and the sea would have taken me too. Oh, if at least I could recreate the people with the paternal arts and infuse souls into bodies made of earth! Now the mortal kind has remained only in the two of us (so it seemed appropriate to the Gods) and we are the only survivors of all humanity.

So he said and in the meantime they were crying; then they decided to pray to the celestial divinity and to ask for help with the oracles. Without delay they went together to the waters of the river Cephissus, which was not yet clear but which was already flowing embanked by its bed. Then, after having sprinkled the water on their clothes and head, they went to the temple of the Holy Goddess; the pediment was livid with repugnant moss and the altars were devoid of fires. As soon as they touched the steps of the temple, both prostrated themselves on the ground and with respectful fear kissed the icy stone and said: “If it is true that the Gods are moved by the righteous, if it is possible to move the wrath of the Gods, tell us goddess Themis, how can we recover from the ruin of our species? Merciful goddess, give us your help because everything has been submerged. The Goddess was moved and gave an oracle: “Come down from the temple, veil your head, untie the belts of your clothes and throw behind your shoulders the bones of the Great Mother.

The two of them were amazed for a long time. Pyrrha first broke the silence and, refusing to obey the goddess’s instructions, apologized and prayed with words of dismay, saying that she was afraid to offend the shadows of the Great Mother by throwing the bones. Meanwhile, the obscure words of the oracle continued to be repeated among themselves, without understanding, brooding. Then the son of Prometheus calmed the daughter of Epimetheus with placid words and said: “How fallacious our intelligence is, the oracles are pitiful and never induce evil, the Great Mother is the earth: I believe that the stones can be called the bones of the body of the earth. We have been asked to throw the stones behind our backs. Even though Pyrrha was impressed by her husband’s interpretation, she actually had little hope. The trust they both had in this divine indication was very low, but what did they have to lose? They came down from the temple, veiled their heads and untied their tunics and threw stones behind their steps as commanded. The stones (who could believe it, if one did not take the ancient writings as witnesses) began to lose their hardness and to soften, and eventually to take shape. Soon, when they were raised and softened, they began to glimpse a human form, very similar to a rough sculpture, as if it had been sketched on marble, but not yet finished. However, a part of them remained damp and earthly with a little liquid, and was transformed into limbs; that which was solid and could not bend was transformed into bones; that which was the vein, remained under the same name; and in a short time, by divine will, the stones thrown by the hand of the man took on a man’s face while, from those thrown by the woman, women were recreated. So we are a hard species that struggles according to our origin.

The earth then spontaneously generated the other forms of life, and after the sun had warmed up with its fire the humidity already present, the wet swamps made the mud rise from the heat, the fertile seeds grew, fed by the vitality of the ground as if they were in the belly of the mother, and began to assume various aspects, similarly to when the seven-mouth Nile leaves the wet fields and brings its rivers back into the ancient course and the newly deposited silt dries up under the ethereal star, and farmers find among the ploughed clods many animals, including some not complete and without all the limbs, in the same animal one part of the body lives, while the other is made from rough soil. Because when the humidity and the heat have mixed, they conceive, and from them, everything comes out. Even if the fire is contrary to water, the hot and humid steam creates everything and the harmony of opposites favors procreation.

Comment

Ovid’s Flood is of rare beauty, offering descriptions and dramatic scenarios, accompanied by the rhythm of the hexameters that now accelerates, now slows down, almost tracing the wave motion, alternating in an expert way dactyls and spondees. I will not describe the details of the sinister Noto, or of Triton’s horn similar to a whirlpool, that are well described by the art of the author in the translation or the original text, but I will try to go to the core of the theological and philosophical message.

Understanding the Flood is not easy. The oldest evidence handed down to us from the classical world comes from Pindar (6th-5th century BCE). Many ancient traditions report this prehistoric cataclysm in their mythologies, like the epic of Gilgamesh of the Sumerians, taken later by the Jewish Torah, or the myth of Manu of the Vedic texts. However, a search of the real meteorological phenomenon, through a comparison of the various narrations, sacrifices the peculiarities of every single tradition. Indeed, each people interprets a fact according to its own cultural, religious and philosophical inclinations, and it is precisely the special elaboration of the story that reveals the starting paradigm. The narration of the flood thus becomes a container where different peoples have expressed their own conceptions of the cosmos and the relationship with the divinity. The flood in “The Metamorphoses” therefore offers us a good example of Greek-Roman thought.

Reading Ovid’s lively description, one can understand that the triggering cause of the flood is to erase the human race because of the abandonment of virtus, or impiety. This is by no means trivial: we read the fantastic descriptions of the text that offer a screenplay that could be used for a science fiction film down to the last detail, not only in the description of the clouds, but also of the guy who is rowing above his house, or the boat that crawls the hull against the seabed made from vines, or the slow and horrible death due to lack of food, or the exhausted birds that let themselves fall into the waves. This is not an allegory, it is not a symbol, but a real situation in the real world. Death. But unlike a science fiction film, the cause is not an asteroid or an attack of ruthless aliens. The cause is the estrangement from the virtus, which caused Jupiter to unleash the elements.

The facts of the flood therefore regard a very close link between the material world and virtus, a link that deserves to be deepened. First of all, we describe a universe without dualism, shared by Gods and humans: there is no spiritual and material world, but we share the same dimension, albeit in different places. Hence the prudence of Jupiter and the consequent decision not to throw lightning, to avoid that the flames can burn even the ether and make everything fall back into a kind of anti-creation, destroying the cosmos and leaving the victory to the dark forces of chaos. Jupiter does not intend to cause an end of the world with a chaotic action by using fire and giving rise to a cosmic conflagration, but exercises its action using only two elements (water and air), excluding the third (fire) to stop the spiral of impiety that is dragging the earth towards chaos and rewrite a new story, in other words to make a clean slate and start again in the direction of order. Let us remember that in the previous section we are told of the danger that men may harm the Demi-Gods and other divine creatures. Furthermore, the confirmation that the flood does not represent a return to chaos but an advancement towards a new order finds its place in the promise of a new humanity made by Jupiter to the divine assembly.

The link between the world, order and virtue is explained by stoic philosophy which, not by chance, offered a great ethical foundation to the reforming action of Augustus and the emperors who followed. The matter of which everything is made, souls and Gods included, is permeated by the logos, which is in charge of the ordaining function. Each of us has within ourselves a part of logos necessary for the logical understanding of the world. Thanks to this component we have an innate sense of justice and live an ethical existence. Hence the virtus is nothing more than the ordering action of the individual in the world and in society, as well as in the empire, in the natural direction of the logos. Virtus is the means by which we participate in the logical ordering of the cosmos. But in stoic understanding, where everything is material, virtue becomes the tangible framework of reality, its order. Stoicism therefore does not propose materialism in the modern sense, but a material spirituality. When human beings move away from virtue, the cosmic order is lost and the universe is affected. Today we could argue that this vision is anthropocentric, however, given that Jupiter, without too many compliments, exterminates the ancient population, it would probably be more correct to consider it logocentric rather than anthropocentric. In fact, when the answer to the logos – from the logical animals – is lost, then the cosmos suffers.

Let’s look around. Our world is sick. It is not to propose a cheap environmentalism, but it is a fact, demonstrated by scientific research and by the logical vision of reality. We have never before had as much technology, knowledge, power in our hands as we do today, and yet we cannot stop the ruin what surrounds us. In fact, it is not science that we lack, but ethics. We have become deaf to logos and as a result our world suffers and animals become extinct because, as in Ovid’s description, the house is one, in common with nature and with the Gods.

A man and a woman are the only survivors in the waters. Deucalion and Pyrrha, irreproachable and just, after crying in the midst of the enormous disaster, decide to purify themselves and go to the ruined temple of the goddess Themis, where not by chance they have found salvation. In fact, the Goddess of Justice does not represent the laws written by men, but something much more sacred: the logos, the justice inherent in the natural order, which also knows how to see the intentions of logical beings and then lets herself be moved by the prayers of honest people.

The way of salvation is communicated by Themis to the two survivors with an oracle, not with a clear order. The oracle requires precisely the logos for its understanding, not an illogical blind faith. Deucalion and Pyrrha have to think long and in the end they use the knowledge of the divine and reasoning to find the answer, because oracles are pitiful and never induce evil (pia sunt nullumque nefās ōrācula suādent), and without conviction, moved by the fact that they had nothing to lose (sed quid temptāre nocēbit?) do what was indicated, throwing behind them stones that turn into new people: in the Greek versions of the myth there is a wordplay between stone (λᾶας) and people (λαός). We, men and women, are made of mud and stone, shaped as works of art by means of a miraculous providence inherent in nature that acts as a sculptor in front of his block of marble: this is probably the greatest metamorphosis of all Ovid’s work.

Animals must also be regenerated: a scientific description follows, based on Lucretius’ theories on the formation of life from heat and humidity.

The world was ready to start again, but a terrible monster appears in the regeneration: the Python. But this is another story.

Mario Basile

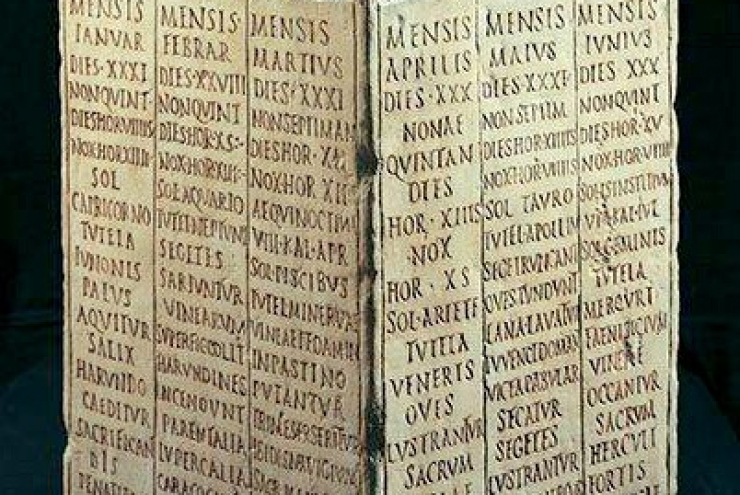

(Fori Hadriani scripsit, Kal Sept. MMDCCLXXII)