Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I, 568 – 779.

Mutations as unbalance of opposite cosmic principles: the myth of Io closes the series on the first book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses and presents a neoplatonic interpretation of the relation between Jupiter and Juno.

I, 568 – 779

- Est nemus Haemoniae, praerupta quod undique claudit

silva: vocant Tempē; per quae Pēnēos ab īmō

- effūsus Pindō spūmōsīs volvitur undīs

dēiectūque gravī tenuēs agitantia fūmōs

nūbila condūcit summīsque adspergine silvīs

inpluit et sonitū plus quam vīcīna fatīgat:

haec domus, haec sedes, haec sunt pēnetrālia magnī

- amnis, in hīs residens factō dē cautibus antrō,

undīs iūra dabat nymphīsque colentibus undās.

Cōnveniunt illūc populāria flūmina prīmum,

nescia, grātentur consōlenturne parentem,

pōpulifer Sperchīos et īnrequiētus Enīpeus

- Āpidanosque senex lēnīsque Amphrȳsos et Aeās,

moxque amnes aliī, quī, quā tulit inpetus illōs,

in mare dēdūcunt fessās errōribus undās.

Īnachus ūnus abēst īmōque reconditus antrō

flētibus auget aquās nātamque miserrimus Īō

- lūget ut āmissam: nescit, vītāne fruātur

an sit apud mānēs; sēd quam nōn invenit usquam,

esse putat nusquam atque animō peiōra verētur.

Vīderat ā patriō redeuntem Iuppiter illam

flūmine et ‘ō virgō Iove digna tuōque beātum

- nesciō quem factūra torō, pete’ dixerat ‘umbrās

altōrum nemorum’ (et nemorum monstrāverat umbrās)

‘dum calet, et mediō sōl ēst altissimus orbe!

quodsī sōla times latebrās intrāre ferārum,

praeside tūta deō nemorum secrēta subībis,

- nec dē plēbe deō, sēd quī caelestia magna

sceptra manū teneō, sēd quī vaga fulmina mittō.

Nē fuge mē!’ fugiēbat enim. Iam pascua Lernae

consitaque arboribus Lyrcēa relīquerat arva,

cum Deus inductā lātās cālīgine terrās

- occuluit tenuitque fugam rapuitque pudōrem.

Intereā mediōs Iūnō dēspexit in Argos

et noctis faciem nebulās fēcisse volucrēs

sub nitidō mīrāta diē, nōn flūminis illās

esse, nec ūmentī sensit tellūre remittī;

- atque suus coniunx ubi sit circumspicit, ut quae

dēprensī totiens iam nosset furta marītī.

quem postquam caelō nōn repperit, ‘aut ego fallor

aut ego laedor’ ait dēlapsaque ab aethere summō

constitit in terrīs nebulāsque recēdere iussit.

- cōniugis adventum praesenserat inque nitentem

Īnachidos vultus mūtāverat ille iuvencam;

bōs quoque formōsa ēst. Speciem Sāturnia vaccae,

quamquam invīta, probat nec nōn, et cūius et unde

quōve sit armentō, vērī quasi nescia quaerit.

- Iuppiter ē terrā genitam mentītur, ut auctor

dēsinat inquīrī: petit hanc Sātūrnia mūnus.

quid faciat? crūdēle suōs addīcere amōrēs,

nōn dare suspectum ēst: Pudor ēst, quī suādeat illinc,

hinc dissuādet Amor. victus Pudor esset Amōre,

- sēd leve sī mūnus sociae generisque torīque

vacca negārētur, poterat nōn vacca vidērī!

Paelice dōnātā nōn prōtinus exuit omnem

dīva metum timuitque Iovem et fuit anxia furtī,

dōnec Arestoridae servandam trādidit Argo.

- Centum lūminibus cinctum caput Argus habēbat

inde suīs vicibus capiēbant bīna quiētem,

cētera servabant atque in statiōne manēbant.

Constiterat quōcumque modō, spectābat ad Īō,

ante oculōs Īō, quamvīs āversus, habēbat

- lūce sinit pascī; cum sōl tellūre sub altā ēst,

claudit et indignō circumdat vincula collō.

Frondibus arboreīs et amārā pascitur herbā,

prōque torō terrae nōn semper grāmen habentī

incubat infelix līmōsaque flumina pōtat.

- Illa etiam supplex Argō cūm bracchia vellet

tendere, nōn habuit, quae bracchia tenderet Argō,

cōnātōque querī mūgītus ēdidit ōre

pertimuitque sonōs propriāque exterrita vōce est.

Vēnit et ad rīpās, ubi lūdere saepe solēbat,

- Īnachidās: rictus novaque ut conspexit in unda

cornua, pertimuit sēque exsternāta refūgit.

Naidēs ignōrant, ignōrat et Īnachus ipse,

quae sit; at illa patrem sequitur sequiturque sorōrēs

et patitur tangī sēque admīrantibus offert.

- Dēcerptās senior porrexerat Īnachus herbās:

illa manūs lambit patriīsque dat oscula palmīs

nēc retinet lacrimās et, sī modo verba sequantur

ōret opem nōmenque suum cāsusque loquātur;

littera prō verbīs, quam pēs in pulvere duxit,

- corporis indicium mūtātī triste perēgit.

‘Mē miserum!’ exclamat pater Īnachus inque gementis

cornibus et niveā pendens cervīce iuvencae

‘Mē miserum!’ ingeminat; ‘tūne es quaesīta per omnēs

nāta mihī terrās? tū nōn inventa reperta

- luctus erās levior! Reticēs nec mūtua nostrīs

dicta refers, altō tantum suspīria dūcis

pectore, quodque unum potes, ad mea verba remūgis!

at tibi ego ignārus thalamōs taedāsque parābam,

spesque fuit generī mihi prīma, secunda nepōtum.

- Dē grege nunc tibi vīr, nunc dē grege nātus habendus.

Nec fīnīre licet tantōs mihi morte dolōrēs;

sēd nocet esse deum, praeclūsaque iānua lētī

aetērnum nostrōs luctus extendit in aevum.’

Talia maerentī stellātus submovet Argus

665 ēreptamque patrī dīversa in pascua natam

abstrahit. ipse procul montis sublīme cacūmen

occupat, unde sedens partēs speculātur in omnēs.

Nec superum rector mala tanta Phorōnidos ultra

ferre potest nātumque vocat, quem lūcida partu

- Plēias ēnīxa est lētōque det imperat Argum.

Parva mora est ālās pedibus virgamque potenti

somniferam sumpsisse manū tegumenque capillīs.

Haec ubi disposuit, patriā Iove nātus ab arce

dēsilit in terrās; illic tegumenque remōvit

- et posuit pennās, tantummodo virga retenta est:

hāc agit, ut pastor, per dēvia rūra capellās

dum venit abductās, et structīs cantat avēnīs.

vōce novā captus custōs Iunōnius ‘at tū,

quisquis es, hōc poterās mēcum consīdere saxō’

- Argus ait; ‘neque enim pecorī fēcundior ullō

herba locō est, aptamque vidēs pastōribus umbram.’

Sēdit Atlantiadēs et euntem multa loquendō

dētinuit sermōne diem iunctisque canendō

vincere harundinibus servantia lūmina temptat.

- Ille tamen pugnat mollēs evincere somnōs

et, quamvis sopor est oculōrum parte recēptus,

parte tamen vigilat. Quaerit quoque (namque reperta

fistula nūper erat), quā sit ratione reperta.

Tum Deus ‘Arcadiae gelidis sub montibus’ inquit

- ‘inter hamādryadās celeberrima Nōnacrīnas

nāiās ūna fuit: nymphae Sȳringa vocābant.

Nōn semel et satyrōs ēlūserat illa sequentēs

et quōscumque deōs umbrōsaque silva feraxque

rūs habet. Ortygiam studiīs ipsāque colēbat

- virginitāte deam; rītū quoque cincta Diānae

falleret et posset crēdī Lātōnia, sī nōn

corneus huic arcus, sī nōn foret aureus illī;

sic quoque fallēbat. Redeuntem colle Lycaeō

Pan videt hanc pīnūque caput praecinctus acūtā

- tālia verba refert – restābat verba referre

et precibus sprētīs fugisse per āvia nympham,

dōnec harēnōsī placidum Ladōnis ad amnem

vēnerit; hīc illam cursum inpedientibus undīs

ut sē mūtārent liquidās ōrasse sorōrēs,

- Pānaque cum prensam sibi iam Sȳringa putāret,

corpore prō nymphae calamōs tenuisse palustrēs,

dumque ibi suspīrat, mōtōs in harundine ventōs

effēcisse sonum tenuem similemque querentī.

Arte novā vōcisque deum dulcēdine captum

710 ‘hōc mihi colloquium tēcum’ dixisse ‘manēbit,’

atque ita disparibus calamīs conpāgine cērae

inter sē iunctīs nōmen tenuisse puellae.

Tālia dictūrus vīdit Cyllēnius omnēs

subcubuisse oculōs adopertaque lūmina somnō;

715 supprimit extemplō vōcem firmatque soporem

languida permulcens medicātā lūmina virgā.

Nec mora, falcātō nūtantem vulnerat ense,

quā collō est confīne caput, saxōque cruentum

dēicit et maculat praeruptam sanguine rūpem.

720 Arge, iacēs, quodque in tot lūmina lūmen habēbās,

exstinctum est, centumque oculōs nox occupat ūna.

Excipit hōs volucrisque suae Sāturnia pennīs

collocat et gemmīs caudam stellantibus inplet.

Prōtinus exarsit nec tempora distulit īrae

725 horriferamque oculīs animōque obiēcit Erīnyn

paelicis Argolicae stimulōsque in pectore caecōs

condidit et profugam per tōtum exercuit orbem.

Ultimus inmensō restābās, Nīle, labōri;

quem simulac tetigit, positīsque in margine rīpae

730 prōcubuit genibus resupīnōque ardua collō,

quōs potuit sōlōs, tollens ad sīdera vultus

et gemitū et lacrimīs et luctīsōno mugītū

cum Iove vīsa querī fīnemque ōrāre malōrum.

Coniugis ille suae conplexus colla lacertīs,

735 fīniat ut poenās tandem, rogat ‘in’ que ‘futūrum

pōne metus’ inquit: ‘numquam tibi causa dolōris

haec erit,’ et Stygias iubet hōc audīre palūdes.

Ut lēnīta Dea est, vultus capit illa priōres

fitque, quod ante fuit: fugiunt ē corpore saetae,

740 cornua dēcrescunt, fit lūminis artior orbis,

contrahitur rictus, redeunt umerīque manusque,

ungulaque in quinōs dīlapsa absūmitur ungues:

dē bove nīl superest formae nisi candor in illā.

Officiōque pedum nymphē contenta duōrum

745 ērigitur metuitque loquī, nē mōre iuvencae

mūgiat, et timidē verba intermissa retemptat.

Nunc dea līnigerā colitur celeberrima turbā.

Huic Epaphus magnī genitus dē sēmine tandem

creditur esse Iovis perque urbēs iuncta parentī

750 templa tenet. Fuit huic animīs aequālis et annīs

Sōle satus Phaethōn, quem quondam magna loquentem

nec sibi cēdentem Phoebōque parente superbum

non tulit. Īnachides ‘matrī’ que ait ‘omnia dēmens

credis et es tumidus genitōris imāgine falsī.’

755 Erubuit Phaethōn īramque pudōre repressit

et tulit ad Clymenēn Epaphī convīcia matrem

‘quō’ que ‘magis doleās, genetrix’ ait, ‘ille ego līber,

ille ferox tacuī! pudet haec opprobria nōbīs

et dīcī potuisse et nōn potuisse refellī.

760 At tū, sī modo sum caelestī stirpe creātus,

ēde notam tantī generis mēque adsere caelō!’

dixit et inplicuit māternō bracchia collō

perque suum Meropisque caput taedasque sororum

traderet ōrāvit vērī sibi signa parentis.

765 Ambiguum Clymenē precibus Phaethontis an īrā

mōta magis dictī sibi crīminis utraque caelō

bracchia porrexit spectansque ad lūmina Sōlis

‘Per iubar hōc’ inquit ‘radiīs insigne coruscīs,

nāte, tibī iūrō, quod nōs auditque videtque,

770 hōc tē, quem spectās, hōc tē, quī temperat orbem,

Sōle satum; sī ficta loquor, neget ipse videndum

sē mihi, sitque oculis lux ista novissima nostris!

Nec longus labor est patrios tibi nosse penātēs.

Unde oritur, domus est terrae contermina nostrae:

775 sī modo fert animus, gradere et scītābere ab ipsō!’

Ēmicat extemplō laetus post tālia matris

dicta suae Phaethōn et concipit aethera mente

Aethiopāsque suōs positōsque sub ignibus Indōs

sīdereīs transit patriōsque adit inpiger ortus.

Translation (*)

There is a forest in Thessaly, called the Tempe, completely surrounded by an impenetrable forest, crossed by the Pineios river that flows with foaming waves from the foot of Mount Pindus. The river, with an imposing waterfall, generates clouds that raise light vapors and bathes the tops of the trees with humidity and dominates nearby places and farther with its roar. This wood is the home, the seat, the sanctuary of a large river, which dwells in a cave made of pointy stones, from where it dominates the nymphs who live in the waves. There first the local rivers are collected, not knowing whether to congratulate the parent or to console him: the Sperchios full of poplars and the restless Enipeus, the old Apidanos and the calm Amphrysos and the Aeas, and then also the creeks gather that carry down, through the path their impetus urges them, the waves to the sea, now tired of wandering.

Only the Inachus river is missing. He, hidden in the bottom of a cave, is feeding the waters with his tears and desperately mourns the missing daughter Io: he does not know whether she is alive or dead, but since he cannot find her anywhere, he is preparing for the worst and believes that she is gone forever. Jupiter, who had seen her while she was returning to her father’s river, had told her:

“O virgin worthy of Jupiter, you that will make happy in marriage I don’t know whom, let us enter together in the shadows of that dense forests (while he was indicating a shady forest) until it is hot and the sun is very high in the sky! In fact, even if you are afraid of getting close to lairs of the fairs, in the forest you will be safe, under the protection of a god, not of any god, but of me, who can hold the celestial scepter with his hand and throw lightning everywhere. But don’t run away!” and instead she started running.

She had already left behind the pastures of Lerna and the fields dotted with trees of the Lyrceia, when the God covered a vast area with fog, blocked her escape and took her chastity.

Meanwhile Juno was peering down on the center of the Argolis region and, surprised that some clouds had quickly clouded the area, on a clear day, she realized that they did not come from the river, nor from the soil moisture, so she looked for her husband, as she already knew his infidelities, because she already caught him many times in the act. And after looking for him without finding him in the skies, she said: “Am I wrong, or is he betraying me?” and, descending from the heights of the ether, she stopped on earth and ordered the clouds to withdraw. But He had foreseen the arrival of his wife and had transformed the appearance of the daughter of Inachus into a luxuriant heifer; even under the guise of a cow, she was still beautiful.

Juno, daughter of Saturn, although striving to examine the appearance of the cow, as if ignoring the truth, asked who she was, where she came from and what her herd was. Jupiter, pretending, said that the cow was born from the earth, so that his wife would stop investigating its origin: then the Saturnia asked for the cow as a gift. What could Jupiter do? Giving up his love would have been cruel, but not giving her would have generated suspicion. On the one hand, embarassment persuaded him, on the other, love. And embarassment would have been overcome by love, but if the cow had been denied as a deceptive gift to her partner for family and marriage, it could have been understood that the cow actually was not an animal! Upon receiving her lover, the Goddess did not lose all fear and suspecting that Jupiter might still steal the cow, entrusted her to custody of Arestor’s son, Argus.

Argo had his head girded with a hundred eyes, of which two at a time rested, while the others keep working vigilant. Whichever way he went, he controlled Io, and even if he turned back he had Io in front of his eyes. During the day it allowed her to graze; but when the sun went down, he closed her up and girded her neck disgracefully with a chain. The unfortunate cow fed on tree branches and bitter grass and instead of sleeping on a bed, she slept on the earth that did not always offer a bed of grass, and she drank from muddy rivers. And even if she had wanted to extend her arms in supplication to Argos, she would not have had arms to extend to him, and when she tried to complain, a bellow came out of her mouth, so that she was terrified with the sounds of her own voice.

Io also went to the banks of the Inachus where she usually played: when she saw the muzzle and the new horns reflected in the waves, she was frightened and ran away upset. The Naiads and Inachus himself ignored her true identity, but she continued to follow her father and sisters and let herself be touched and admired. Old Inachus handed her some grass and she licked her father’s hand and kissed his palms and did not hold back the tears and if only the words followed, she would have asked for help and revealed her name and condition; but instead of words the letters, which she wrote on the sand with her paw, offered the sad clue to his father that her body had been changed.

“Miserable me!”, father Inachus exclaimed while he was embracing the horns and neck as white as the snow of the moaning heifer and kept complaining:

“Miserable me! Are you really my daughter whom I have been looking for everywhere? It would have been better if I had never found you, because my suffering would have been milder! You are silent and silent you don’t answer me when I speak, only you breathe deep sighs in your chest and all you can do is bellow at my words! Actually I prepared the thalamus and the wedding, hoping to have a son-in-law first and then grandchildren. But now your consort will come from a flock and your son will come from the flock. Not even with death can my pain end, being a god does not help me, since the death threshold is precluded to me, my agony will last forever. ”

While the father was crying in this way, Argos with sparkling eyes pushed him away by tearing his daughter from him and dragging her to other pastures. Then Argos got to the top of a mountain, from where sitting could look everywhere. But the King of the Gods could no longer tolerate so much evil for Io, from Phoroneus. So he called Mercury, the son that the bright Pleiad had given him, ordering him to kill Argos. Shortly thereafter Mercury with wings on his feet had already picked up the wand that caused sleep and put the helmet on his hair. As soon as he was prepared in this way, he jumped down from his father’s fortress towards the earth; there he took off his helmet and laid his wings, keeping only his wand with him: then with this, like a shepherd, he began to lead some stolen goats, as he proceeded along the remote countryside, and meanwhile he played a pan flute of carved reeds. Argos, the guardian of Juno, fascinated by the new sound, said to him:

“Hey you, whoever you are, could you sit with me on this stone? In fact, there is no other place where grass is more fertile than this and where the shade is more suitable for shepherds “.

Atlas’ son sat down and talking for a long time entertained him all day while playing the pan flute, trying to win his vigilant eyes. But Argos continued to fight against the sweet sleep and, although the drowsiness had conquered one part of his eyes, the other part nevertheless continued to watch. Then Argos asked him how the pan flute was invented, which in fact was a recent invention at the time. And then the God replied:

«Under the icy mountains of Arcadia, among the Hamadryas of Nonacres, there was only one very famous naiad: the nymphs called her Syringe. She had managed to escape the satyrs more than once while they followed her and also excaped all the gods and those who lived in the shady forest and in the fertile countryside. She worshiped Diana, the goddess Ortigia, keeping virginity like her; and she dressed just like Diana so much that she could be confused with Latonia, if it had not been for her horn bow instead of gold, but even so she could be confused. One day, on his way back from the Lyceum hill, Pan with his head covered with pine needles saw her and spoke to her – and there was nothing left to do but to tell how the nymph, despised his entreaties and fled to inaccessible places, until she reached the placid course of the sandy Lado; but there, since the river prevented her from continuing to escape, she prayed to the sisters of water to transform her, and when Pan thought he could hold her, instead of the body of the nymph he embraced marsh reeds and therefore he sighed, but his breath on the reeds had generated a sweet sound, like a moan. The God, captured by the sweetness of the tone of the new discovery exclaimed: “In this way I will always be able to talk to you” and thus gave the name of the girl to the instrument made of reeds of different length held together by a little wax.»

While Mercury was telling all this, the God of Cyllene noticed that Argos’ eyes had given way and they had all closed for sleep. Mercury immediately stopped speaking and sealed the languid eyes with sleep by his magic rod. As Argos faltered, he struck him without delay with his arched sword, where the head joins his neck, and threw him off the cliff, all bloody, smearing the impervious rock. By now you were lying dead Argos, and that light you had in all your eyes had gone out and one night now occupied a hundred eyes. The Goddess Saturnia, Juno, collected them and placed them on the feathers of her sacred bird, adorning its tail with sparkling gems. The Goddess then ignited with anger and without delay hurled the hideous Erinyes over the eyes and heart of the Argolic rival and thrust blind terror into her chest, tormenting her all over the earth. And you, Nile, remained as a last resort for this suffering; as soon as Io arrived, she knelt on the edge of the shore, straining her neck high, as she could, looking up at the stars she seemed to turn to Jupiter with moans and tears and mournful bellowing to beg for the end of her sufference. Eventually Jupiter throwing his arms around the consort’s neck begged her to end the punishment and said:

“Do not fear for our future anymore: it will never again cause you any pain” by calling the Styx marshes as a testimony. As soon as the Goddess subsided, Io began to resume the appearance it had before: the fur disappeared from the body and the horns narrowed, her eyes became smaller and her muzzle contracted, her arms and hands returned, and the hooves dividing into five parts turned into nails: nothing remained of the bovine form except its whiteness. The nymph, happy with the restituted function of her two legs, got up afraid of speaking, fearing that a bellow would rise up like a heifer, and timidly tried to express words as once she used to do.

Even today Io is celebrated as a very popular goddess by a crowd dressed in linen. In short, it is believed that from her, fertilized by the seed of the great Jupiter, Epaphus was generated, to whom temples were dedicated in various cities together with his mother. Phaeton, born of the Sun, was equal to him in value and age. Once Epaphus could not bear that Phaeton boasting to be superior to having Phoebus as his father. Inachus’ grandson said to him, “Stupid, you believe everything your mother tells you and you are proud of a wrong idea about your father.” Phaethon blushed and held back the anger with shame and reported to Climene, his mother, the insult of Epafo and said:

“The fact that I, who am straightforward, who am proud, I had to keep silent, should give you the greatest pain! I am ashamed that he was able to insult me in this way while I was unable to respond. But you, if I was truly born of a heavenly race, manifest a proof of my noble origin and welcome me into the sky! ” and he put his arms around his mother’s neck and asked her on his head and on Merope’s, on the sisters’ wedding, to give him a sign of his true father. Clymene, it is not known if moved more by the prayers of Phaeton or rather by the anger of the offense caused, stretched both arms to the sky and looking at the light of the sun said:

“My son, I swear to you on this glorious splendor of dazzling rays, which listens to us and looks at us, that you are the proper son of the Sun you are seeing, precisely of the Sun that warms the earth. If I am lying, may He deny me the sight and may this be the last light I see! And your suffering of not knowing the paternal home will soon end. The land, where your father lives and from where he stands, borders on ours: if you have courage, go ahead and ask him himself.”

Phaeton, immediately after the words of his mother, jumped happily. He left his land of Ethiopia while imagining the ether with fantasy, then he went through India under the heat of the sun and reached the place where his father was abiding.

Comment

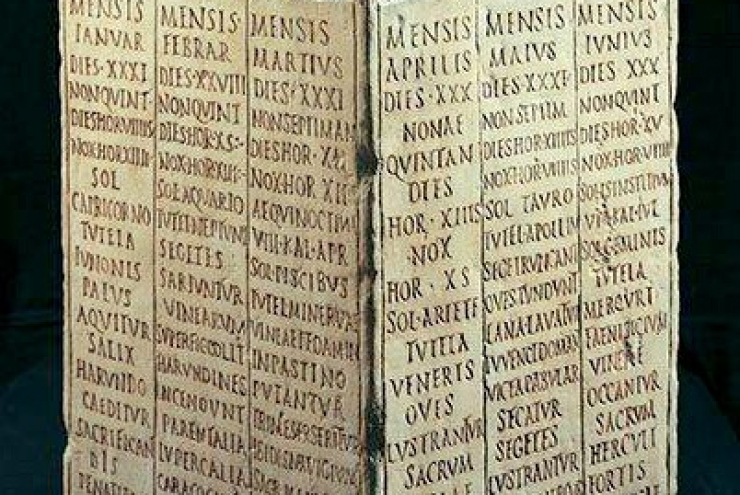

There is a natural order, where everyone feels secure in their role, position and rules. We humans are always looking for this order, more or less consciously, at the cost of self-imposing unwritten rules, such as the time we go to eat or sleep, or the number of teaspoons of sugar in the coffee, or the amount of sweetener, or any of our hundreds of small habits. We love the rules, they make us move in harmony with others, we love to take refuge in the lukewarm security of custom. For years I have observed how the sequence of arrival at the workplace, even when there is a flexible schedule, is always the same, regardless of the place. When you make an appointment with four friends, you can predict the order of arrival with a good level of confidence, because there is who always arrives early, who always arrives on time, who arrives five minutes late and who can not do without his academic quarter of an hour delay. In the family, customs become the frame on which our existence unfolds, trying to put barriers against unwanted changes. Natural order, in fact, involves social and also religious habits. Nobody forces us to perform a ritual, but the search for cosmic harmony and the Pax Deorum simply conforms to us, natural, innate, as well as the periodic scanning of the calendar, with its festivals and seasons.

It seem that the cyclical repetition of actions and situations puts us in tune with the concept of stability and eternity. After all, the continuation of a tradition, or of a festivity in the calendar, transcends our own earthly existence, providing us with the pretext for expanding our time horizon.

However this plot of regularity is not enough to contain the horizon of our lives, nor the cosmic horizon. There is a great impulse of change, often creative, which operates in everything. A dynamic of unrepeatable events develops on the cyclical nature of the calendar: history. On a cosmic level, the power that induces the explosion and emanation of the universe from transcendent uniqueness, along the direction defined by the growing entropy, is personified by the overwhelming force of Love, Eros, Amor, to which nothing resists, neither animals, nor humans, nor Gods. Eros is the undisputed engine of change, of metamorphosis, free from any calculation, subversive, antisystem, chaotic. The unexpected that changed generations’ plans. Love for the Romans was as much courtship as a disruptive love passion, cosmic lust. The script repeated several times by Ovid is that of a woman or a nymph, who wants to resist the cosmic force, devoting herself to virginity, rejecting every man, and thus ending up attracting the attentions of a God, with a law of retaliation: Apollo with Daphne and Pan with Syringe. In the case of Io this propensity to virginity does not appear, considering that the father had other plans for her. If on the one hand girls and nymphs are transformed into animals and trees, on the other the Gods are also affected by the consequences, albeit in a less dramatic but equally profound form. Apollo adopts laurel as its symbol, that is, as part of its very essence. Jupiter himself transforms into various animals to indulge the impulse of love.

We, readers of Ovid, are not immune to it, it is only a matter of recognizing it. How many transformations have we faced in our life following the chaotic intervention of Love? Bumping into Eros breaks the balance of our lives and upsets the previous order, the routine, fragmenting our existence with a sequence of “before” and “after”, tumblers and pirouettes, comedies and tragedies, jealousies and crazy passions, fun and reckless facts, new environments, new tours, often new cities, new regions, new countries. At the beginning of a love story you feel that sense of vertigo of the things that really happen, or unwillingly, bearing the bitter consequences, or they charge us with the illusion of riding the mighty wave of events, with a surfboard in precarious balance. These are the moments when we feel the acceleration of metamorphoses in our lives.

The power of Love is not limited to human passion, to our psychological and social sphere, but has its roots in the very process of the existence of the cosmos, according to neoplatonic metaphysics. The first cause of the cosmos, by definition, is the One, purely transcendent, unparticular, who is not the “Creator”, otherwise it would be directly knowable through his work (remember the controversy between Porphyry and the Christians). The One is characterized simultaneously by its existence and its energy. Its existence is the Limit Principle, which provides each entity with its definition, stability, limit and identity. Its energy is the principle of the unlimited, the principle of expansion without limit, the power that can be transferred by binding the whole cosmos. These two principles are the cause of every definition and change in the universe and propagate from the transcendent unity at every level of existence, manifesting themselves as a characteristic also in the Gods and Goddesses. In this metaphysical key, Jupiter impersonates the propagation of the creative power that would continue unlimited, while Juno represents the limitating and regulatory principle.

While clashing with the static creationism of monotheistic religions, these two neoplatonic philosophical principles are reflected in Darwin’s evolutionism. Multiplication and differentiation which, however, is not blind but balanced by rules. In fact, despite this engine of continuous differentiation, we do not see a continuum of indefinite living beings, mutations of mutations around us, but for each living being we clearly identify order, family, genus and species.

However, Ovid warns us, sometimes something happens and balance is lost. When the creative action is not balanced by the function of the limit, new life forms are generated, mutations that can be monstrous, of which the last lethal virus that appeared in this pandemic can be understood as an example. The spread of the virus, according to the limitless principle, must be stopped with containment, the limit principle.

Obviously the balance is valid in both directions: if, instead, the principle of the limit overwhelms that of the unlimited, the life would stagnate, there would be no more procreation and the species could face extinction. In this sense, mythology shows the delicate balance between definition and action, which forms a structure for life itself and the entire universe.

The narrative of Io’s metamorphosis unfolds in a complex way. The theme is introduced from an oblique perspective, with the absence of Inachus from the meeting with the other rivers. Inachus cries inside his cave for the disappearance of his daughter. He does not know what has happened, but we are informed by a flashback that the nymph has been transformed into a cow by Jupiter. It was probably a temporary change, but Juno’s intervention, who watches over the Status Quo of the cosmos, leads to a stalemate, precisely according to the concept of limit, sealed by Argos, as a guarantee of no return. The transformation is atrocious. As in the case of Lycaon, seen a few chapters ago, the victim suffers from the inability to speak. The horror is amplified because Io always remains aware, of the bitter grass that eats, of the silty water that drinks, of her bellowing, so gloomy and speachless. The human part, which continues to make her aware and make her suffer, pushes her to write with her paws on the ground to be recognized by her father, before being dragged away by Argos.

Ovid, with his genius, slows down the narrative by inserting the myth of Syringe, which although taking up the theme of the transformations due to love, seems almost an interval with respect to the dramatic tension of the Io’s story. But when Argos’ eyes close and we are now distracted and relaxed in the shadows together with the shepherd who plays the pan flute, suddenly a sword stroke bloody the scene, as in a Tarantino’s film, speeding up the events.

There are few cases in mythology where a metamorphosis is reversed: the best known is the episode of Ulysses and the sorceress Circe. Also in that case the god Mercury intervened in favor of those who underwent the metamorphosis. Here the God breaks the barrier of the limit imposed by Juno to encourage the return of being to a higher state, from animal to human, a well-known function of Mercury. The intervention in this case is only a first but fundamental step for the liberation of Io from its metamorphosis. The killing of Argos leads to the height of the crisis, where the exhausted Io, tormented by Juno, kneels on the banks of the Nile, being she the daughter of a river, and stretches her neck to heaven (another human aspect). Jupiter therefore takes pity and restores the cosmic order with his consort: as soon as the anger of Juno is placated, that is, as soon as the Peace of the Gods is restored, Io resumes its human form, giving us a happy resolution.

Io is not a secondary mythological figure. The cow is a lunar symbol and the identification of Io with the goddess Isis, often depicted as a white cow, therefore offers a bridge to Egyptian mythology by expanding the horizon of myth in a syncretist perspective. Other sources tell us how Io, before reaching the Nile, passed through the Ionian Sea, which took its name from her, and when she arrived in Egypt she gave birth to the sacred ox Apis, while she ascended into heaven as a celestial cow. The mysterious connection between the water and the moon takes us to an archaic time, where the Bacchantes, invaded, erupted shouting “Io, Io!”, Which means “hurray”, custom that we find in the auspicious “Io Saturnalia “. Io’s story is interwined in a world context of the Great Mother and Sacred Cow, with Kalì-ma, Isis-Hathor and Brigid. By opening the narrative on a plane that goes far beyond the borders of the Empire, Ovid begins to tell the story of Phaeton, of his journey from Ethiopia to India and beyond. But for this story we will have to wait for the second book of the Metamorphoses.

Mario Basile

Fori Hadriani scripsit, Prid. Id Apr. MMDCCLXXIII [CEREALIA]

(*) Mario Basile’s translation from Latin.

Article translated from original article in Italian by the autor.