Ovid’s Metamorphoses I, 434 – 567: Apollo e Daphne.

I, 434 – 567

- Ergo ubi dīluviō tellus lutulenta recenti

- sōlibus aetheriīs altōque recanduit aestū,

ēdidit innumerās speciēs partimque figūrās

rettulit antiquās, partim nova monstra creāvit.

Illa quidem nollet, sed tē quoque, maxime Pȳthon,

tum genuit, populīsque novīs, incognite serpens,

- terror erās: tantum spatiī dē monte tenēbās.

Hunc Deus Arquitenens et numquam tālibus armīs

ante nisi in dammīs capreīsque fugācibus ūsus

mille gravem tēlīs, exhaustā paene faretrā,

perdidit effūsō per vulnera nigra venēnō.

- Nēve operis fāmam posset dēlēre vetustās,

instituit sacrōs celebrī certāmine lūdōs

Pȳthia perdomitae serpentis nōmine dictōs.

Hīc iuvenum quīcumque manū pedibusque rotāve

vīcerat, aesculeae capiēbat frondis honōrem;

- nōndum laurus erat, longōque decentia crīne

tempora cingēbat dē quālibet arbore Phoebus.

Prīmus amor Phoebī Daphnē Pēneia: quem nōn

fors ignāra dedit, sed saeva Cupīdinis īra.

Dēlius hunc nūper, victō serpente superbus,

- vīderat adductō flectentem cornua nervō

‘quid’ que ‘tibī, lascīve puer, cum fortibus armīs?’

dixerat, ‘ista decent umerōs gestāmina nostrōs,

quī dare certa ferae, dare vulnera possumus hostī,

quī modo pestiferō tot iugera ventre prementem

- strāvimus innumerīs tumidum Pȳthōna sagittīs.

Tū face nesciō quōs estō contentus amōres

inrītāre tua nec laudes adsere nostrās.’

Fīlius huic Veneris ‘fīgāt tuus omnia, Phoebe,

tē meus arcus’ ait, ‘quantōque animālia cēdunt

- cuncta deō, tantō minor est tua glōria nostra.’

Dixit et ēlīsō percussīs āëre pennīs

inpiger umbrōsā Parnāsī constitit arce

ēque sagittiferā prompsit duo tēla pharētrā

dīversōrum operum: fugat hōc, facit illud amōrem;

- quod facit, aurātum est et cuspide fulget acūta,

quod fugat, obtusum est et habet sub harundine plumbum

hoc deus in nymphā Pēnēide fixit, at illo

laesit Apollineās traiecta per ossa medullās:

prōtinus alter amat, fugit altera nomen amantis

- silvārumque latēbris captivarumque ferārum

exuviīs gaudens innuptaeque aemula Phoebes;

vitta coercēbat positōs sine lege capillōs.

Multī illam petiēre, illa āversāta petentes

inpatiens expersque virī nemora āvia lustrat

- nec, quid Hymen, quid Amor, quid sint cōnūbia, cūrat.

Saepe pater dixit ‘dēbēs mihi, nāta, nepōtes’:

illa velut crīmen taedās exōsa iugālēs

pulchra verēcundō subfūderat ōra rubōre

- inque patris blandīs haerens cervīce lacērtis

‘dā mihi perpetuā genitor carissime,’ dixit

‘verginitāte fruī: dedit hōc pater ante Diānae.’

Ille quidem obsequitur: sed tē decor iste, quod optās,

esse vetat, vōtōque tuō tua forma repugnat.

- Phoebus amat vīsaeque cupit cōnūbia Daphnes,

quodque cupit, sperat, suaque illum orācula fallunt;

utque levēs stipulae demptīs adolentur arīstīs,

ut facibus saepēs ardent, quās forte viātor

vel nimis admōvit vel iam sub lūce relīquit,

- sic Deus in flammās abiit, sic pectore tōto

ūritur et sterilem sperandō nūtrit amōrem.

Spectat inornātōs collō pendēre capīllōs

et ‘quid, sī cōmantur?’ ait; videt igne micantes

sīderibus similēs oculōs, videt oscula, quae nōn

- est vīdisse satis; laudat digitōsque manūsque

bracchiaque et nūdōs media plus parte lacērtōs:

sī qua latent, meliōra putat. Fugit ōcior aurā

illa levī neque ad haec revocantis verba resistit:

‘nympha, precor, Pēnēi, manē! non insequor hostis;

- nympha, manē! sīc agna lupum, sīc cerva leōnem,

sīc aquilam pennā fugiunt trepidante columbae,

hostēs quaeque suōs: amor est mihi causa sequendī!

mē miserum! nē prōna cadās indignave laedī

crura notent sentēs et sim tibi causa doloris!

- Aspera, quā properās, loca sunt: moderātius, ōrō,

curre fugamque inhibē, moderātius īnsequar ipse.

Cui placeās, īnquīre tamen: nōn īncola montis,

nōn ego sum pāstor, nōn hīc armenta gregēsque

hōrridus observō. Nescīs, temerāria, nescīs,

- quem fugiās, ideōque fugīs: mihi Delphica tellūs

et Claros et Tenedos Patarēaque rēgia servit;

Iuppiter est genitor; per mē, quod eritque fuitque

estque, patet; per mē concordant carmina nervīs.

certa quidem nostra est, nostra tamen ūna sagitta

- certior, in vacuō quae vulnera pectore fēcit!

Īnventum medicīna meum est, opiferque per orbem

dīcor, et herbarum subiecta potentia nōbīs.

Ei mihi, quod nūllīs amor est sanābilis herbis

nec prōsunt dominō, quae prōsunt omnibus, artēs!’

- Plūra locutūrum timidō Pēnēia cursu

fūgit cumque ipsō verba īnperfecta relīquit,

tum quoque vīsa decens; nudābant corpora ventī,

obviaque adversās vibrābant flāmina vestēs,

et levis īnpulsōs retrō dabat aura capillōs,

- auctaque forma fuga est. Sed enim nōn sustinet ultrā

perdere blanditiās iuvenis deus, utque monēbat

ipse Amor, admissō sequitur vestīgia passū.

Ut canis in vacuō leporem cum Gallicus arvō

vīdit, et hīc praedam pedibus petit, ille salūtem;

- alter inhaesūrō similis iam iamque tenēre

spērat et extentō stringit vestīgia rostrō,

alter in ambiguō est, an sit conprensus, et ipsīs

morsibus ēripitur tangentiaque ōra relinquit:

sīc deus et virgo est hīc spē celer, illa timōre.

- quī tamen insequitur pennīs adiūtus Amōris,

ōcior est requiemque negat tergōque fugācis

inminet et crīnem sparsum cervīcibus adflat.

Vīribus absumptīs expalluit illa citaeque

victa labōre fugae spectans Pēneidās undās

- ‘fer, pater,’ inquit ‘opem! sī flūmina nūmen habētis,

quā nimium placuī, mutandō perde figūram!’

vix prece fīnitā torpor gravis occupat artus,

mollia cinguntur tenuī praecordia librō,

- in frondem crīnēs, in rāmos bracchia crescunt,

pes modo tam vēlox pigrīs rādīcibus haeret,

ōra cacūmen habet: remanet nitor ūnus in illa.

Hanc quoque Phoebus amat positāque in stīpite dextrā

sentit adhūc trepidāre nōvō sub cortice pectus

- conplexusque suīs rāmōs ut membra lacertis

oscula dat lignō; refugit tamen oscula lignum.

Cui Deus ‘at, quoniam coniunx mea non potes esse,

arbor eris certē’ dixit ‘mea! semper habēbunt

tē coma, tē citharae, tē nostrae, laure, pharetrae;

- tū ducibus Latiīs aderis, cum laeta Triumphum

vōx canet et vīsent longās Capitōlia pompās;

postibus Augustīs eadem fīdissima custōs

ante fores stabīs mediamque tuēbere quercum,

utque meum intonsis capūt est iūvēnāle capillīs,

- tū quoque perpetuōs semper gere frondis honōres!’

fīnierat Paean: factīs modo laurea rāmīs

adnuit utque capūt vīsa est agitasse cacūmen.

Translation

The earth, covered with mud from the recent flood, as soon as it was heated by the ethereal sun and its strong heat, generated many species, partially recovering the forms of the ancient animals before the flood and partly creating new monsters. Even if the earth did not have the intention, then it generated you, the mysterious snake, the terror of the new peoples: so great was the mountainous area you were occupying.

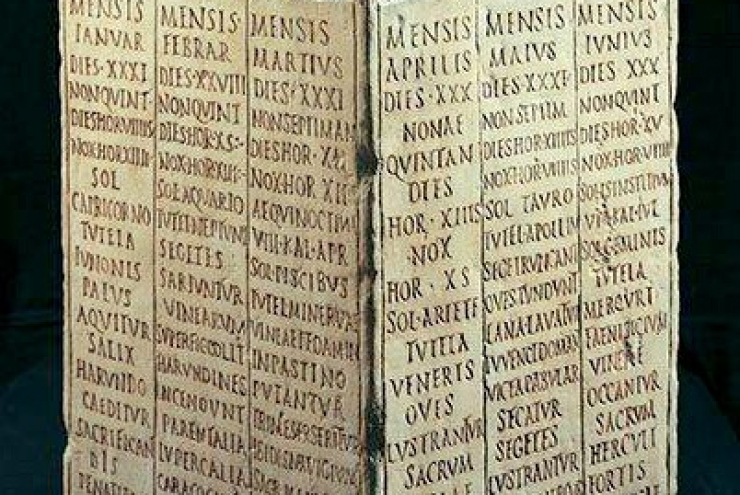

The Archer God, Apollo, almost making his quiver empty, killed this violent monster by spreading the black poison to the wounds inflicted by a thousand arrows, which he had previously used only against deer and goats. And to prevent the oblivion of the fame of its deeds, it established the sacred games with the famous competition, called Pythian by the name of the defeated serpent. In these games anyone among the young athletes who won with their hands, feet or chariots, received the honour of the crown of Aesculapius; the laurel wreath was not yet used and Phoebus used to crown his long hair head with a crown made from any type of plant.

Daphne of Peneus was the first love of Phoebus: it didn’t happen by pure chance, but for the violent impetus of Cupid. The Delian, proud of the recent victory over the snake, when he saw Cupid flexing the ends of the stretched bow told him: “Insolent little boy, what do you want to do with those powerful weapons? Those are suited to the shoulders like mine: I can mortally wound the wild beasts and the enemies and I have just shot down the terrible Python with many arrows, while he was oppressing with his belly a large part of the countryside. You, on the other hand, be content with lighting with a torch whatever lovers but do not arrogate the praises that are due to me”. The son of Venus, said: “Phoebus, your bow can pierce everything, but my bow will pierce you. You’ll see that your glory is as inferior to mine as all animals are inferior to a god.”

As soon as he spoke these words, cleaving the air with the beating of wings, he put himself upright on the shady Mount Parnassus and drew two arrows with different effects from his quiver: one caused love refusal, the other caused falling in love; the arrow that caused falling in love was of shining gold with a sharp tip, while the one that caused the rejection of love was rounded with lead in the shaft. The God pierced Daphne, the nymph daughter of Peneus with the latter, while with the first pierced Apollo’s marrow through the bones: immediately he fell in love, but the other escaped from the lover without even wanting to know his name, preferring, like the virgin sister of Phoebus, the hiding places in the woods and the trophies of the wild beasts she hunted; a band gathered her dishevelled hair. Many wanted her, but she kept herself free, after having hastily refused the suitors, wandered into the impervious forests and did not care what Hymenaeus, Love and marriage were. Many times her father had told her: ‘You must give me grandchildren’: but she, who hated the wedding torches as if they were a crime, blushed in modesty in the beautiful face and hugged her father’s neck and said flattering: ‘Dear Dad , allow me to remain a virgin forever: even Diana’s father granted her this desire. He accepted, but that very beauty of yours forbade you to be what you wanted and your appearance resisted this vow.

Phoebus had fallen in love with Daphne and, after seeing her, wanted to join her hoping to get what he wanted, deceived by his own oracles; and as the light straw separated from the wheat ears is burned, and as the hedges burn, when a wayfarer accidentally puts the torch too close or leaves it there, so the God became inflamed with love and his whole chest went up in flames, fed by a sterile hope of true love. The God watched her unadorned hair go down her neck and said: “How would her hair be if it were combed?”; he saw her eyes that sparkled with flames like the stars, he saw her lips, but was not satisfied only to see them, and he praised her fingers, her hands, her arms and her shoulders, more than half naked: if something was hidden, he imagined it even more beautiful. But she escaped faster than a light breeze and did not stop at his call: “Nympha, daughter of Peneus, please stay! I do not follow you as an enemy; wait nymph! So the lamb escapes from the wolf, the doe from the lion, so the doves escape with the trembling feathers from the eagle, each from his enemies: but the reason for my pursuit is love! Poor me! Be careful lest you fall, that the brambles do not ignobly scratch your legs and hurt you! The places for which you are running are inaccessible: please run slower, hold back your escape, I myself will chase you more slowly. But at least ask yourself who is following you! I am not a mountaineer, I am not a shepherd, here I am not keeping herds and herds. You don’t know it, you recklessly, you don’t know who you are running from and you continue to flee because you don’t know him: I own the lands of Delphi, Claros, Tenedos and the Patare; Jupiter is my father; I can manifest what was, what is and what will be. Thanks to me the strings of the instruments play in harmony. My arrows have a sure hit, but even surer is that single arrow that wounded me in the empty chest! I invented medicine, and I am called the rescuer of the world and I have the domain of the powers of herbs. Poor me, because love cannot be healed by any grass. The arts that help everyone can’t help their lord.”

The daughter of Peneus with a frightening race continued to run away from him who wanted to talk to her and left him with his speeches in half, but she looked beautiful even then; the wind stripped her, the breezes that came towards her shook her clothes and the air gave her light impulses to her hair moving them back and her beauty grew in her escape. But the young God could no longer bear to waste time in flattery and, as Love himself warned, followed in the footsteps of the young woman with a hasty step. Like a hunting dog that has seen a hare in a deserted field and runs behind its prey, while the hare seeks salvation; in that situation the pursuer expects to capture the prey at all times and keeps the muzzle pointed in the footsteps, while the other is in difficulty, fearing to be captured and avoids its bites and escapes the jaws that try to grab it: so it happened to the God and to the virgin, the first fast, fed by hope, the second by fear. But he was faster, because he was pressed and incited by the wings of Love, and without giving her rest he reached the shoulders of the fugitive and by now he had his breath on her neck with sparse hair. She abandoned her strength, turned pale and overcome by the weariness of the exhausting escape, looking at the waves of the Peneus she said: “Father, help me! Rivers, if you are divine, let me lose my form, which I never liked! ‘As soon as the prayer ended, a heavy numbness struck her limbs: the soft breasts were surrounded by a soft bark, the hair turned into leaves, the arms grew in the shape of branches, the feet, so fast before, fixed themselves like lazy roots, the face became the top of the tree: only beauty remained in her.

Phoebus continued to love her even so, and after placing his right hand on the trunk, he could still feel her chest beating under the new bark and embracing the branches with his arms, as if they were limbs, he kissed the wood; but even so the wood kept on avoiding kisses. And the God said to her: “since you cannot be my bride, you will certainly be my tree! My hair, my harps, my arrows will always have you, Laurel; you will be with the leaders of Latium, when the happy voice will sing the Triumph and the Capitol will contemplate the long processions; you yourself will be the most faithful guardian in the doors of Augustus’s palace, on the doorposts, and you will protect the oak in the middle, and as my head is youthful with thick hair, so will you always bear the honor of your fronds. He had finished: he beckoned to the newly generated branches and it seemed that she had shaken the top as if it were the head.

Comment

After the flood and the restoration of the human race, narrated in the episode of Deucalion and Pyrrha, Ovid describes in natural terms the metamorphoses of the other living beings, remembering how in the muddy lands of the Nile, when the floods retreat, the Egyptian shepherds find in the mud strange animals. The earth is repopulated naturally, either by recovering the animals that existed before the cataclysm, or by generating new life forms, including the terrible monster Python. For Ovid, therefore, nature was not necessarily “good”: it was easy in antiquity to die for natural phenomena such as storms, fires, floods or come across wild beasts such as lions, bears, snakes. Thinking about it, even today mother nature, benign in many ways, can put us in danger in a thousand ways; however, our awareness of having violated the natural order, with the exploitation of resources and pollution, blindfolds us to the point that we believe that everything natural is also good. In reality, we still enjoy a rational Apollonian shield against the negative aspects of nature. For example, without vaccines we would be at the mercy of the smallest and most dangerous natural monsters, viruses. If we consider that vaccines are a medical product, therefore linked to the action of Aesculapius-Apollo, we realize that Apollo keeps on defending us and harmonizing with its arts the chaotic aspect of Nature represented by Python. The same concept of harmony is noetic. It is true that in nature there are important regularities, but harmony has a completely mathematical, abstract basis: in nature there is no “music” understood as a succession of sounds subjected to rigid rules of mathematical ratios of frequencies arranged according to a certain rhythm.

The god Apollo is therefore the great epic figure who, in line with the design of Jupiter, establishes order in the world. Even his ability to see the future proceeds from celestial harmony, from perceiving from his eternity the future projections that escape us, for our living in a fragmented reality.

There would be all the premises for a great Apollonian monotheism, with a divinity capable of maintaining order, of offering salvation, of presenting the final prophecy. The One, the Sun, the Revelation. Yet the exhilarating epic can be a mental trap, as if the frantic search for sunlight could dazzle us so much that we can no longer perceive the dark abysses of the irrational, where every victim can fall. The rational mind does not have the tools to identify what is not rational. This is a masterful lesson of polytheism, where different forces interpenetrate one another in search of a dynamic balance, visible as a sequence of contrasting events in the temporal plane, or paradoxical myths in the poetic tale. So don’t be shocked by the story where a God falls victim to a love story: at stake is the eternal confrontation between the solar and ordering force and the dynamics of the erotic principle. A brat, a plump little boy with a bow, almost a comic figure. The mind mocks him. But he, Eros, Cupid, moves the world effortlessly: Gods, men, animals. Polytheism welcomes and recognizes the erotic and irrational component next to the Apollonian one, without having to take part in the confrontation, to invent the fable of Evil that ruins the plans of the Good, a fable that by introducing the sense of the diabolical is diabolical in its imbalance and blindness, in his alienation of the human being, in his introduction of the sense of guilt linked to the necessary and natural sexuality.

Apollo used a thousand arrows to kill Python, Cupid fired only one towards Apollo and the other towards Daphne: the first, the God who orders and harmonizes nature, the second, the one who refuses love. How many plans, how many alliances, how many events have changed because of love. Our lives have been profoundly modified by Cupid’s arrows, if only for the fact that we exist here and today as the result of an erotic act. We plan our life rationally until a look, an encounter, a gesture is amplified in our brain so that we choose the irrational. In Apollo’s story, we move abruptly from an epic style to the elegiac scene of the frustrated lover for denied love, not only a theme but even a program for all of Ovid’s work, where the effort to achieve unrequited love generates situations with a thousand nuances.

Once struck, Apollo focuses only on his goal, the nymph Daphne. There is no fight against Cupid, nor resistance, nor resentment. Apollo knows well that he was hit by the arrow, he says it to Daphne herself during the chase, but the erotic power goes beyond the bones, straight into the marrow, into the nerve centre, into the personality. Love acts as an irrepressible inner strength that gives God the speed to reach his beloved who is fleeing. It’s a well-known story: how many times have we heard each other – or have we said – “let it go, it’s not the right person for you”? But the awareness of the arrow generally does not deviate the course of the lover, otherwise it would be an easy matter and the poets would not waste rivers of ink. Daphne’s description through the eyes of the lover is as brilliant as sensual: “… he saw her lips, but was not satisfied only to see them, and he praised her fingers, her hands, her arms and her shoulders, more than half naked… “.

The contrast with the epic is at its best when Apollo, after trying to explain to the fugitive not to have bad intentions but to have fallen in love, tries to convince her by revealing her honours. The situation becomes almost comical due to the striking contrast between the condition of God and that of the rejected lover.

Is it permissible to speak thus of the Gods? Plato and philosophers generally disagreed and considered ancient myths as non-educational. On the other hand we cannot deny the fact that a serious reflection can lead to interesting results, which eventually enrich our perception of the divine. The recognition of the erotic force in the universe is surely a point of primary importance. Furthermore, the myths transfer images of the divinity without which we would run the risk of losing all the colours, the information of every God, turning to a generic, not characterized philosophical and abstract divinity.

At the end of the chase, Daphne prefers to escape her suitor, asking for help (fer opem) from her father. However, in Ovid’s plot the river gods, unlike the Olympic and Titanic deities, do not have the power to perform transformations. Perhaps for this reason Tellus intervenes to help the girl, turning her into a laurel. Eventually the human part within the laurel calms down into the noblest design of God. Ovid leaves unsolved if Apollo’s triumph is Daphne’s defeat or victory. A fairly common ambiguity that perhaps has no answer.

This section of metamorphoses, in addition to presenting an epic, naturalistic and elegiac part, also offers the explanation of various customs following the aetiological style of Callimachus and the Alexandrian school: the foundation of the Pythian games, the reason why during those games a branch of oak was offered instead of laurel, the narration of how the laurel became the sacred plant to Apollo and evergreen, and with the reference to the triumphs and the home of Augustus brings the reader back to the time when the work was written.

An intense story, which reminds us of heart-rending falling in love, suffering without remedy, illusory situations, but above all it shows us that, no matter how hard we try, life is not just rational events, but also disruptive energies that can suddenly change the course of carefully planned events. And if passing by a laurel plant you’ll happen to feel a thrill, you already know the reason.

Mario Basile

(Fori Hadriani scripsit, Id. Nov. MMDCCLXXII)