Metamorphoses by Ovid. I, 76-112: Human beings and the Golden Age

I, 76-88 “Dē genere hūmānō”

- Sanctius hīs animal mentisque capācius altae

dēerat adhūc et quod domināri in cētera posset:

natus homo est, sīve hunc dīvīnō sēmine fēcit

ille opifex rērum, mundī meliōris orīgo,

- sīve recens tellus sēducta nūper ab altō

aethere cognātī retinēbat sēmina caelī;

quam satus Īapetō mixtam pluviālibus undīs

finxit in effigiem moderantum cuncta deōrum,

pronaque cum spectent animālia cētera terram,

- ōs hominī sublīme dedit caelumque vidēre

iussit et ērectōs ad sīdera tollere vultūs.

Sīc modo quae fuerat rudis et sine imāgine, tellus

induit ignōtās hominum conversa figūrās.

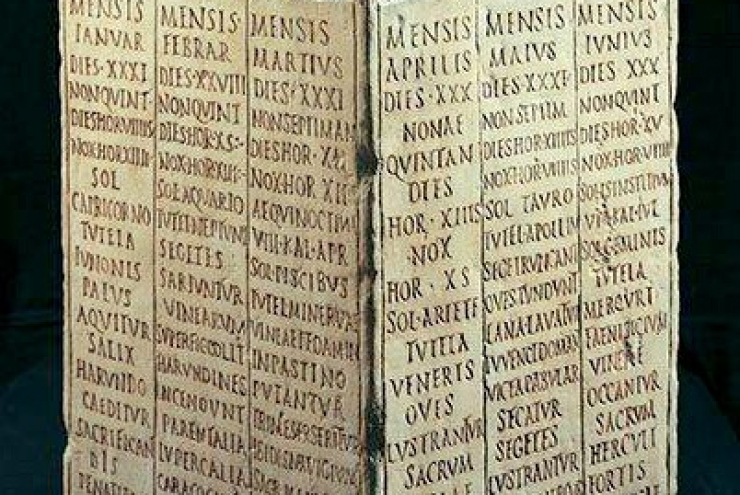

I, 89-112 “Dē aetāte aureā”

Aurea prīma sata est aetās, quae vindice nullō,

- sponte suā, sine lēge fidem rectumque colēbat.

Poena metusque aberant nec verba minantia fixō

aere legēbāntur nec supplex turba timēbat

iudicis ōra suī, sed erant sine vindice tūtī.

Nondum caesa suīs, peregrinum ut vīseret orbem,

- montibus in liquidās pīnus descenderat undās,

nullaque mortalēs praeter sua lītora nōrant.

Nōndum praecipitēs cingēbant oppida fossae,

nōn tuba directī, non aeris cornua flexī,

nōn galeae, nōn ensis erat: sine mīlitis ūsū

- mollia sēcūrae peragēbant ōtia gentēs.

Ipsa quoque inmūnis rastrōque intacta nec ullīs

saucia vōmeribus per sē dabat omnia tellūs,

contentīque cibīs nullō cōgente creatīs

arbuteōs fētus montānaque frāga legēbānt

- cornaque et in dūrīs haerentia mōra rubētīs

et, quae dēciderant patulā Īovis arbore, glandēs.

Vēr erat aeternum, placidīque tepentibus aurīs

mulcēbant Zephyrī nātōs sine sēmine flōrēs;

mox etiam frūgēs tellūs inarāta ferēbat,

- nec renovātus ager gravidīs cānēbat aristīs:

flūmina iam lactis, iam flūmina nectaris ībant,

flāvaque dē viridī stillābant īlice mella.

Translation

The Human Race

Until that moment, among the animals there was no more capable and more skillful in the intellect, which could dominate over others: man was born. Either the Architect of the universe, who was the origin of the better world, did it with a divine seed, or the young Earth, just separated from the high ether, kept the seed of the kinsman sky. The son of Iapetus (Prometheus) modeled the earth mixed with rainwater in the image of the gods that govern everything. And while all the other animals look to the ground, he gave the men a lifted face and ordered them to look up to the sky and raise their gaze to the stars while standing upright. Thus, the land that had been until recently raw and without image, changed in this way, was populated by human figures who still knew nothing.

The Golden Age

The age of gold first began, in which confidence and justice spontaneously were exercised without the need for a guarantor and without laws. There was no punishment or fear, nor could there be threats printed in the bronze, nor a crowd of pleading people feared the words of his judge, but they were all safe even in the absence of any authority. Pinewood did not descend on the clear waves to see the world, after being cut from its mountains, and mortals knew nothing beyond their own shores. Steep ditches still did not surround the cities, there was not yet the tuba, straight forged in the bronze, nor the curved horns, nor the galleys, nor the swords: without the use of the army, the people used to live a quiet peace and in safety. Even the land itself, uncontaminated and untouched by the rake, nor plowed by any plow, gave everything spontaneously and the men, happy with the effortlessly picked up foods, used to gather arbutus, wild strawberries, cornelian cherries, blackberries attached to the hard oaks and acorns, which fell from the great tree of Jupiter. There was an eternal spring and the placid zephyrs caressed the flowers born without seed with warm breezes; in fact the earth, even if not cultivated, often offered fruit and the field, even without rest, was lightened by the abundance of spikes: rivers of milk and even nectar flowed, blond honey dripped from the green holm-oak.

Comment

Man, like everything in the universe, has a divine foundation, in full agreement with what we previously read, where rivers, seas, mountains, and valleys were the direct work of divinity.

Ovid offers us two very different explanations on the origin of man. In the first hypothesis explains the human origin directly with the action of God, through a “dīvīnō sēmine”, with a divine seed. This hypothesis appears in continuity with the previous verses, recalling in verse 79 with “mundī meliōris orīgo” the “genesis” of the world of verse 21, where we quote the “melior nātūra”.

In the second hypothesis, however, the formation of man appears almost accidental and in a position of discontinuity with respect to the previous divine program. A piece of Earth (mother-like Gaia, chthonic component, material, and feminine), who retains the seed of Uranus (celestial and masculine component) received as rain, is molded by Prometheus, the Titan, in the image of the Gods. It is remarkable that the male and female components combine harmoniously as a necessary condition for the birth of humanity, which is natural in the classical polytheist perspective, where the pantheon is populated by male and female deities, with the latter not necessarily subjected to the first. The point instead of breaking with the previous order is revealed by the text “Sīc modo quae fuerat rudis et sine imāgine, tellus induit ignōtās hominum conversa figūrās”. The description of the earth as rough and without an image recalls the primordial chaos, something that was thought to have been relegated to the past. Moreover, the intervention of Prometeus confirms the titanic component in the human being, where it is known that in the classical world the Titans represented the primordial forces of the universe, prior to the ordering action of the Olympic gods. Ovid thus casts a dark shadow of tension that will manifest itself in the following text, characterized by the “fall” from the golden age to the later phases.

Be that as it may, the distinctive trait of the man-woman is that it has been shaped “in effigiem deōrum moderantum cuncta” in the image of the Gods who govern everything. The characterization of the Gods as those who govern everything defines the main characteristic of the newly formed human being, as he who aspires to govern everything according to his divine nature, and therefore not as a pure receptor of divine power but as a potential actuator. To look up at the sky and the stars, to wonder about the divine and philosophical questions is an all-human trait, which goes beyond pure biology and its sphere, but expresses an aspiration to return to that heaven from which perhaps the earth has received the seed, or that divine form, which assumes a transcendental connotation.

The first steps of human beings are in ignorance, in non-knowledge (ignōtās figūrās), in primordial innocence, in primitive and childish ingenuity. Which is neither painful nor obscure; on the contrary, it gives rise to a happy age, the Golden Age.

All of us, as probably also Ovid, sometimes dream, perhaps after a long day of work stress, to return to our childhood, where the unawareness of life’s difficulties, of the future loss of our loved ones, of the inconsistency of the world, still were totally unknown and far beyond the absolute safety of the enclosure of a small playground. Well, the charm of the Golden Age lies in this ignorant security in a context free from danger. Mortals do not build ships yet, rather they only know the coasts of the village where they were born (nullaque mortalēs praeter sua lītora nōrant), nor do they feel the desire to explore because all they need is within reach. Plenty of food, mild weather, spontaneous crops. In Ovid’s paradigm, we are not the result of a natural selection, where we had to engineer and evolve to compete with the fairs. On the contrary, according to Ovid, our progenitors were happy with what they had and did not need anything, they were not nomads but sedentary and gathered the fruits that the earth gave them spontaneously, without the need for agricultural work. Because everyone had everything, there were no wars.

In the description of the Golden Age, unnatural exploitation of nature is presaged when it is said: “pinewood did not descend into the clear waves to see the world, after having been cut from its mountains”. The contrast of the pine cut from the mountain to the sea denounces a subversion of the natural order: one of the first signs of civilization is the deforestation and exploitation of nature for technological and economic purposes. A sinister image that today reminds us of the tragedy of world deforestation, but that certainly also in the times of Ovid could be observed with the great works of urbanization throughout the empire. The natural order of things of the Golden Age is described as the absence of human wickedness represented by ditches around cities, weapons, and trumpets of war. It may surprise how the absence of agriculture is mentioned in the golden age. However, the hard work of the fields, the boundaries that are naturally associated with the fields themselves, are elements that already require a level of development that leaves the enclosure of primitive ingenuity. We did not own anything in the Golden Age, because we lived in harmony with the nature that offered us everything.

But things changed, they precipitated, making the genesis of mankind as the central point of the chiasm: from chaos to man and man to chaos. We will therefore see the spectacular fall in the next article.

Mario Basile

Malacae scripsit, IX Kal. Ian. MMDCCLXXII

Un pensiero riguardo “The Metamorphoses by Ovid: The Golden Age”

I commenti sono chiusi