INTRODUCTION

It is possible to individuate two intertwined, but distinct, dimensions in the religious conception of Cult in Ancient Rome, the Public Cult, linked to the welfare of the Roman State, and Private or Domestic Cult. This presentation aims to briefly illustrate the ancient sources of the contemporary Roman Private Cult, showing its most significant elements.

Before moving to the analysis of the various components of the contemporary Roman Private Cult we practice, few words must be spent on the nature of the sources we choose to mention in this excursus. Due to time restraint we shall mention only the most notorious and specifically relevant elements from the archaeological and literary material at our disposal. We hope to give an overview of the ancient sources of the contemporary Roman Private Cult as much comprehensive as possible.

Our main focus will be on the Roman Rite (“Ritus”). The “Ritus” is considered the maximum expression of the Roman religiosity or “Pietas” and thus distinguished the private cult in ancient Rome. The “Ritus” is a performed form of pray and worship. It consists in the combination of “formulae” (words) and gestures (actions) that have to be repeated in specific patterns. The better the gestures are performed and the lines recited, the better the pray is. J. Champeaux confirms in her book “The Religion of the Romans” that the Roman “Pietas” demanded absolute respect of the rite which consists in the “exact recitation of the Prayer” and “impeccable execution of the Gestures” (Bologna, 2002, pp. 11-16).

Following Aulus Gellius, the Roman jurist of the 2nd century , who, in his “Noctes Atticae”, depicts the roman citizens who observed the “Religiones”, the ritual acts and words, “really rigorous” and also “really prudent”, we will now proceed to examine the salient components of the Roman Private Cult.

PRIEST

The “Pater Familias”, the senior male lead and head of the “familia”, the Roman domestic nucleus, is invested with the highest religious authority for what the private cult is concerned. This bit of information is clearly stated by an earlier source Albius Tibullus, who is known for having composed “Elegiarum”, I, X, 15-28, 1st century.

At the edge of the house, the venerated authority of Pontifex stops, the head of the family is the absolute arbiter: “Suo quisque ritum sacrificium faciat”; Each one celebrates his Rite (C. Terentius Varro, “De Lingua Latina”, VII, 88).

“Separatim nemo habessit deos neve novos, neve advenas, nisi publice adscitos; privatim colunto quos rite a patribus acceperint. Ritus familiae patrumque servanto”/ No one has special, new, or foreigner divinities unless they are publicly recognized; in private are cultivated the Cults that are received according to the Rite of the Fathers. The Rite of the Family and of the Fathers is to be preserved (M. Tullius Cicero, “De Legibus”, II, 8).

ABLUTIONS

The actual “ritus” is always preceded by ablutions. Those who would have performed the “ritus” are compelled to purify themselves. They literary have to wash themselves with water. The Romans believe that the water has the power to erase the past and restore, even if just for moments, the original purity of the ritual practitioners. Because water is believed to purify and regenerate, ablutions have to precede the religious acts, preparing the man to enter what is sacred.

Ablutions are common practice, for example they are performed before most kind of sacrifices (M. Eliade, “Treatise on the History of Religions”, Turin, 2008, page 176). One of the most important testimonies is given to us by P. Vergilius Maro in the Aeneis (IV, 634-640): “Bid her hasten to sprinkle her body with river water and bring with her the victims”,

A. Theodosius Macrobius refers to ablution in several occasion: firstly, in Saturnalia. II, 1, 2 reminds us of Aeneas who, once washed in the water of the Tiber River is purified and so he can invoke Jupiter. Then in Saturnalia III, 2, 6: “… we know that, when someone is about to sacrifice to the Heaven’s Gods, this one has to purify himself with the ablution of the body. On the other hand, when it is necessary to sacrifice to the Underworld’s Gods, a simple sprinkling is considered sufficient”.

P. Ovidius Naso in the Fasti (IV, 7, 78): “Wash your hands in the river water” for the pastoral ceremony in honour of the Goddess Pale.

COVERAGE OF THE HEAD (Velatio Capitis)

But let’s enter the real elements of the “Ritus”. First thing first, the pater familias has to cover his head with a strip of his toga (P. Chini, “Life and Customs of the Ancient Romans – The Religion”, Rome, 1990, archaeological evidences page 75 photo 62, Relief with scene of sacrifice – National Roman Museum; page 54, photo 52, Augustus sacrificing with a saucer (“pàtera”) – Vatican Museums). Ploùtarchos in his “Quaestiones Romanae”, 22″ referring to the imperial practice of velatio capitis states: ” They Sacrifice to Cronus (Saturn) with the head discovered perhaps because was Aeneas the man who had introduced the custom of covering the head and indeed Crono’s sacrifice is very ancient”. But why do the Romans cover their heads while venerating the Gods? Ploùtarchos provide us with an answer “In sign of humiliation or rather to avoid that some unhappy and insulting voice come to them from the outside while they are praying “. Or even to symbolize “the disappearance and the concealment of the soul by the body “.

SILENCE

The first formula of the Rite is the “Favete Linguis”, command of silence. As Seneca explains in “De vita beata” (26, 7): “When you will hear the sacred texts mentioned, keep silent.” In the latin text Seneca uses the world “favoriteci” which derives from another important latin term which is “favor”. In this case, the term doesn’t mean favour or help, but it is an order that intimates silence, the silence needed to perform the sacred rite according to the prescriptions, alias without being disturbed by any profane voices “. We can find variants of this formula in Vergilius (“Aeneis”, V, 71): “ore favete omnes”, that means that all have to observe silence, and in Tibullus (“Elegiarum”, II, 2, 2): “The bystanders, men and women, have to observe a pious silence” and (in II, 1, 1) “keep silent all the bystanders “.

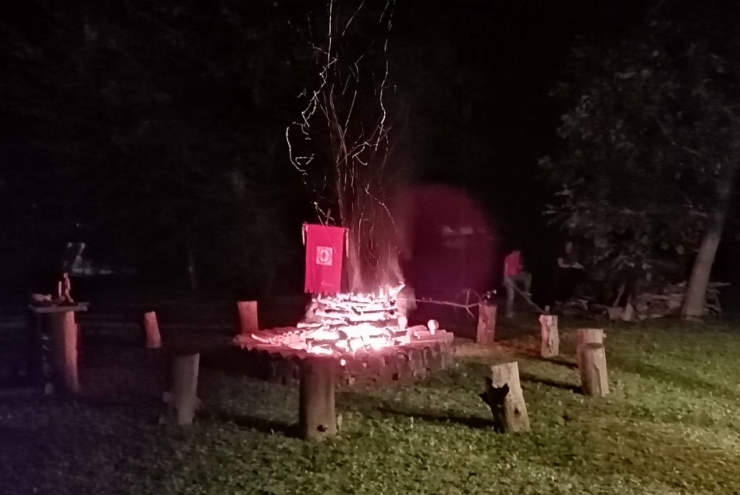

IGNITION OF THE SACRED FIRE

As soon as silence has been imposed, we read again in “Elegiarum”, II, 2, 3 of Tibullus: “Sacred incense must be offered to the fireplace”, implying obviously, the previous ignition of the sacred fire.

In the “Fasti” of Ovidius (VI, 291, 304) Vesta identifies herself as the flame of the domestic fireplace.

DELIMITATION OF THE SACRED SPACE

Then, the place designated for the ritual has to be purified. A procession, led by the pater familias, followed by the participants to the rite, walked in an hourly circle around the space that has to be purified. This part of the ritual is a remant of the more archaic magical-religious notion of the protective circle (J. Champeaux, “The Religion of the Romans”, Bologna, 2002, page 84).

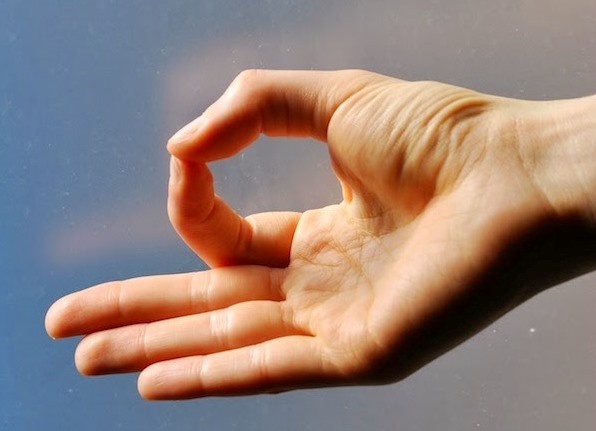

ADORATION (Adoratio)

Right index and right thumb together are brought to the lips and they are softlly touched with a kiss; then the right arm tends forward in greeting and/or touches the sacred image (Titus Livius, “Ab Urbe Condita”, V, 22, 4 and Minucius Felix, “Octavius”, II, 4).

GREETING

The physical gesture is accompained by different version of a common formula “Salvete Dii”, “Salvete locurum Deos”, “Salve Sancte Pater”, “Salve Magne Pater salve”. Many are the sources we could refer you to, but let’s just mention Ovidius and his “Fasti” and “Carmina Epigraphica”.

PRAYER

At this point, the pray begins. The Romans would worship one or more deities at one time.

The main source of roman prey (“Precatio or Preces”) is the “Carmen”, in which several formulae of invocation are repeated and grouped together forming a rhythmic prose.

M. Porcius Cato in his “De Agri Cultura” (141) provides us with examples of praying. One of the most famous formulae is: “Mars Father I’m asking and I’m begging you to be benevolent and propitious for me, for our house and for our family”.

First of all the invocation specifies to which divinity it is addressed and secondly it draws the God’s attention by calling him by his own name. The divine name is isolated and repeated. Then, we have the request formulated in an iteractive, enchanting way: two pairs of synonyms, two verbs and two adjectives and immediately after three nouns to indicate the beneficiaries of the solicited benevolence (J. Champeaux, “The Religion of the Romans”, Bologna, 2002, pp. 86-87).

Then we have the formula that accompanies the offer to God: “for this purpose … accept the offer of this bun...” (A Giano). The Romans were known for their scrupulousness. They coined a formula, for the occasion in which they would be uncertain about the outcome of the rituals : “If nothing has satisfied you, take these (successive offers) for expiation”.

They even had a formula “Sive Deus, sive Dea” – whether you are a God or a Goddess (Cato, “De Agri Cultura”, 139), for the case in which the sex of the evoked deity was unknow. In order not to irate the “Nume”, they would prudently include both eventualities (J. Champeaux, “The Religion of the Romans”, Bologna, 2002, p.46).

There is a specific order in the invocations to group of Gods. Firstly they would invoke Janus God of every beginning. Immediately after Jupiter, father of all the gods, then the other minor deities would follow. Leaving Vesta, the goddes of the fireplace, as the last. : M. Tullius Cicero (“De Natura Deorum”, II, 67): “They wanted Giano to be the first in the sacrifices … the power (of Vesta) concerns the areas and the fireplaces and therefore every prayer and every sacrifice end up there, indeed she protect everything that is intimate “.

Apotropaically, during the Rite nothing is to be crossed as Ovidius wisely prescribes “do not cross the legs on the knee” (“Fasti”, IV, 827-828).

Ritual prayer is based on the effective force of the word, for this reason errors, stuttering and the substitution of one word with another are factors that annul the Rite (G. Plinius Secundus, “Naturalis Historia”, 28, 10; II, 74, in D. Forte , “The priest in Rome”, Forlì, 2015, p.41). We can find examples of private prayers in Tibullus, To Lari (“Elegie”, I, X, 15, 28); in Cato, To Marte Silvano, To Giove, To Giano, To Marte, (“De Agri Cultura”, 83, 131-132, 134, 139, 141); in the works of T. Maccus Plautus, To Fides, To Jupiter, To Apollo, To Domestic Lare, To Penati. Often the testimonies are also archaeological: epigrams on tombstones, inscriptions in verses on the herms (“Carmina Epigraphica”, I-IV century): To Diana, To Silvano, To Camene, To Priapo; prayers of the Latin Anthology on codes of the III-V century: To Tellus, To Sole, To Marte, To Libero.

HYMNS

Several well known roman poets composed hymns to honour one or more Gods. Among them, we mention “to Venus” in T. Lucretius Carus (“De Rerum Natura”, I, 1-49);

To Diana, Hymenaeus, Venus in G. Valerius Catullus (“Carmina”, 34, 61, 36);

To Libero, Ceres, Mars, Flora and Pale – Ovidius (“Metamorphoseon”, IV, 17-30, V, 341-661 and “Fasti”, V, 549-598, V, 183-378, IV, 723-776 );

To Mercury, Apollo, Fortune, Bacchus, Faunus, Diana, Venus in Q. Horatius Flaccus (“Carmina”, I 10, I 31, IV 6, I 35, II 19, III 25, III 18, III 22, I 30, IV 1;

To Aesculapius, Janus, Jupiter, Mercury, Nymphs, Saturn in M. Valerius Martialis (“Epigrammaton”, IX 17, VIII 8, X 28, VII 60, VII 74, IX 58, XII 62);

To the Sun, to Minerva, to Juno in Martianus Capella “De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii”, II 185-193, II 149, VI 567-575).

OTHER FORMULAS

Other famous formulae survived.

“Quod bonum, faustum, felix, fortunatum, salutareque sit” – ‘be this thing good, auspicious, happy, lucky and healthy’ as Cicero reports in “De Divinatione” (I, 182). In this work Cicero also explains how these words may bear prophetic value.

The Salii, the priests of Mars handed down for generations an archaic rhythmic chant addressed to Giano:

“O Zeul, ad oreso omnia, Verom ad patulcie, Cosmis es ianeos, Ianes es duonos, Ceros es Manos “; ‘Oh Sun rise in the world! Oh You who are opening the Heaven’s door! You are such as a kindly concierge, you are the good Giano, you are the beneficial governor”.

It is difficult to understand it completely but, once adapted and translated, this is used in our private cult for the ritual consecration of the new cult objects.

OFFERS

Three are the most common offers to the gods.

Incense : “Give me … the honor of welcome incense … around the fireplace” (S. Aurelius Propertius, “Elegie”, IV, 6, 4-5). “And to me, I would like to celebrate the Patrii Penati and to offer incense to my old Lare every month” (Tibullus, “Elegiarum”, I, 3, 33-34).

Wine : “Three times she pour limpid wine above the fire” (Vergilius, “Georgica”, IV, 384) or “Pouring wine as you say these words” (Ovidius, “Fasti”, II, 638).

Libation: “(Pouring) The wine from the amphorae to honor you, with copious supplications you associate with the Lares” (Horatius, “Carmina”, IV, 5, 33-35).

They could be combined “I’m offering … to you, Giano, wine and incense” (Ovidius, “Fasti”, I, 172-173).

There were also other types of offerings:

“At the time of Calends a woman … opens … the Lari locked up … covers the sacellas with flowers … and the sabina grass (a substitute of the incense) catches fire on the old fireplaces” (Propertius, “Elegiarum”, IV, 3, 53-58) .

“At the God Termine’s feast… he threw three times wheat into the fire” (Ovidius, “Fasti”, II, 651). It is recurrent the idea of burning the offerings to the gods. This suggests that the fireplace could become an aisle or domestic Altar.

It would be decorated with crowns and fronds and eventually washed down with daily libations. “everyone quickly offer a libation on the table and pray to the Gods” (Vergilius, “Aeneis”, VIII, 278-279). On the days of Calende, of the Ides, of the None, Cato prescribes to adorn the fireplace with a crown of laurel and make offerings to the Lare, tutelary domestic deity (“De Agri Cultura”, 143)

TABLE – BANQUET (Ara)

The banquet is transformed into a sacred domestic ritual of communion with the divine, and the table becomes an altar. Ploùtarchos (“Quaestiones Romanae”, 64) reminds us that the romans would never eat everything that was served, the table was never to remain empty. He explains one should not allow a sacred thing to remain empty, and the table being sacred should not either.

Sacred images would have been placed on the table to make the deities present at meal (Ovidius, “Fasti”, VI, 305-306). In festivities, such as the Saturnalia, sharing a meal was also part of the religious ceremony.

HOME ALTAR (Lararium)

The Lararium, is the shrine before which the private domestic ritual must be celebrated. Private shrines can be of different kinds: a small building at the bottom of the home garden; a closet with niches for the gods, a very little shrine or some underground votive rooms. The most common type is the shrine, closed with doors.

Inside the Lararium we would normally find the images of the deities and the objects necessary for the Rite.

Domestic deities.

The Lares. They are the patrons of a humanized space: e.g. they would dominate over a property, a house (Lar Familiaris), the sea once navigated (Lares Permarini), but also intersections (Lares Compitales), etc .. Originally, the Lare would always appear in the its singular form (Cato, “De Agri Coltura”, 143). It was usually depicted as a dancing young boy with long hair, short tunic, mug in one hand and a sacuer called pàtera in the other.

The Penates. They are deities linked to people, protective of the dispensation of the house (Penus) and of the nourishment of the family; consequently they are the protector gods of the family.

The Genius is the guardian god of Pater Familias and he is depicted in a anthropomorphic way (man in toga) or as a snake.

The Mani, finally, are the deified ancestors who are to be honored.

Artefacts and boxing memo

Numerous archaeological evidences as well as Vergilius, (“Aeneis”, VI, 230), give us the list of votive furnishings that are used for the Rite.

Among these we find the thurible, the incense box and the pàtera we have mentioned before (which is a saucer to present the offerings to the Gods), the jug for wine and the aspersorium (the olive or laurel twig).

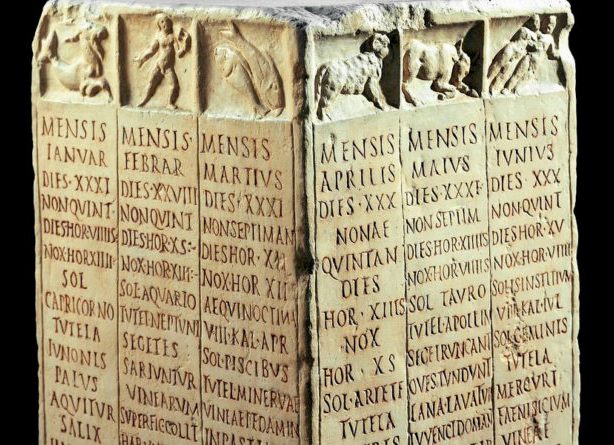

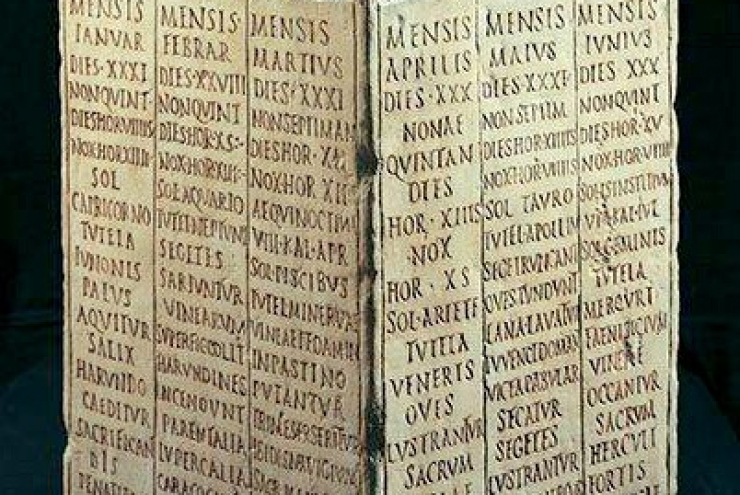

CALENDAR

We would like to conclude mentioning the sacred character behind the Roman calendar, calendar codified by Julius Caesar and still current today in the world with the same names.

The Roman religious year begins with the month of March, sacred to Mars (God of war and dear to Romans because father of the Roman progenitor Romulus). It is considered the propitious season for the beginning of the wars and the time for warlike feasts.

In April (from the latin “Aperire”), the month sacred to Venus, the Goddess who blooms, agricultural feasts dominated.

May, sacred to Maia, Goddess of abundance, is the moment of the glories, but also the period for funerary procession.

June, sacred to Juno Goddess, with its ceremonies, prepares for the harvest.

In July, Iulius Caesar month, the demons of the woods and the deities connected to the water are venerated.

In August, the month dedicated to the first imperator Octavianus Augustus, in addition to the harvest feasts, beneficial heat is celebrated.

September, seventh month, is dedicated to equestrian games.

October, eight month, marked the end of the war campaigns, then there are ceremonies of lustration of arms as well as feasts related to the harvest.

November, ninth month, is not important for agriculture and it does not contain any holidays.

In December, tenth month, the holidays are linked to sowing and to the sun.

January, besides being the month dedicated to Giano, it does not bear any particular characteristics.

In February, the month of purifications, dedicated to the God Februo, is the last month and is dominated by expiation ceremonies.

As a literary source it will be sufficient to mention the elegiac narration of Ovidius in the Fasti, which collect and illustrate with great erudition the legends and historical episodes linked to the individual occurrences of the Roman Calendar.

Un pensiero riguardo “The sources of the Roman Private Ritual”

I commenti sono chiusi