I don’t remember how I happen to know the “Platonic Theology” by Proclus. I found that fat volume maybe for chance, maybe for fate, or for the will of a daemon. During my reading I found an incredible logic construction that was explaining the great divine metaphysics, revealing the philosophical aspects of every divinity of the classic world in the frame of the Neoplatonic Mystic. It was an ancient wisdom that was capturing and intoxicating my mind, like a good wine. Unfortunately, after the reading, I felt the same symptoms of drunkenness: amnesia, confusion, lack of clarity. What was going on?

I don’t remember how I happen to know the “Platonic Theology” by Proclus. I found that fat volume maybe for chance, maybe for fate, or for the will of a daemon. During my reading I found an incredible logic construction that was explaining the great divine metaphysics, revealing the philosophical aspects of every divinity of the classic world in the frame of the Neoplatonic Mystic. It was an ancient wisdom that was capturing and intoxicating my mind, like a good wine. Unfortunately, after the reading, I felt the same symptoms of drunkenness: amnesia, confusion, lack of clarity. What was going on?

Let’s say it once and for all, Proclus and friends’ texts are not the best for a relaxing evening reading. If on the one hand Plato’s dialogues bring us smoothly to the heart of the philosophical thought, on the other hand Neoplatonic scripts are populated with abstruse terms like “substance”, “participation”, “power”, “characteristic”, “formal cause”, making the text very hard to newcomers. Difficulty is also caused by words that today are in use with a different meaning. For instance, if we understand the word “power” used by Proclus as “capacity of a system for doing work” (physics), we misunderstand the whole subject. Therefore it is very important to use the correct definition and to exactly understand each term. This is the only way to enjoy the gigantic logic construction of the great minds of Plotinus, Porphyry, Iamblichus, Proclus and Damascius.

As a matter of fact, Neoplatonism is the synthesis of centuries and centuries of philosophic research, run in Phoenicia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, etcetera, giving life to the top philosophic synopsis of the whole ancient world. This is the reason why its vocabulary and its concepts require preparation. For similarity sake, studying Proclus without knowledge of the previous steps, is like trying to solve the integrals without knowing the multiplication tables.

With this consideration in mind, I start a review of the classic philosophy, with simplicity and humility, trying to identify the great themes that are useful for the understanding of the Neoplatonic Metaphysic. It is a hard task, my knowledge is very limited, but I hope to be able to solve the issue step by step. If you wish to come with me, it will be my pleasure to walk together along this path. I have nevertheless to point out that it will be a concise divulgation for newcomers, probably useless for the experts: the light rise of my path could be boring to an expert rock climber.

DOES EVERYTHING CHANGE? DOES ANYTHING CHANGE AT ALL?

Neoplatonism is full of worlds, of layers of reality, one on top of the other. What is the origin of such an interpretation of the reality? Which was the first layer?

Two great thinkers before Plato presented positions that were apparently incompatible.

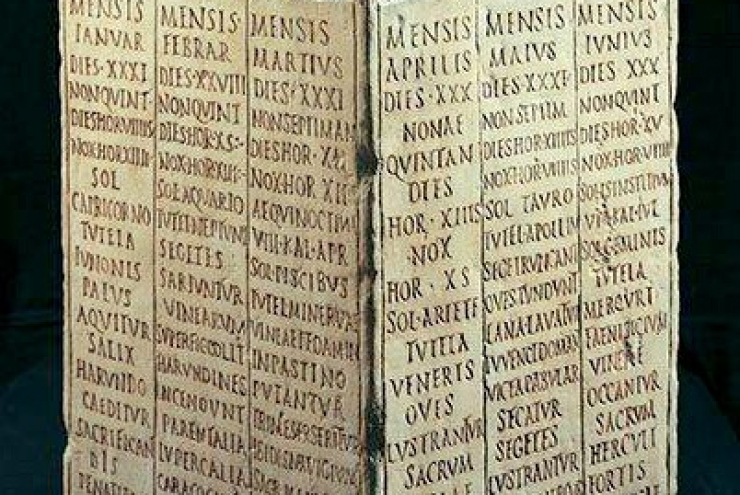

Heraclitus of Ephesus, the philosopher with obscure language, who lived between the 6th and the 5th century BCE, dwelling in the beautiful temple of Artemis the goddess in Ephesus, studied nature and observed the eternal changing and transformation. He told that “you cannot descend twice into the same river”. Water keeps on flowing and is continuously replaced, like all the reality: everything flows like a river (πάντα ῥεῖ ὡς ποταμός).

Heraclitus extrapolated the value of his observations (everything changes) and made it a cosmological principle. As a matter of fact we are dealing not with a pure observation but with an extrapolation, because according to the knowledge of that time there were in nature objects that did not follow this always-changing rule, like for instance the stars and constellations in the sky that, during a human life span, look steady. It is strangely easier to support the Heraclitus’ principle today than in the past. Today, thanks to science, we can identify changes on temporal frames that are much longer than our own existence, like geological eras or cosmological time (billions of years). The Sun, once a symbol of uniqueness and eternity, today is understood as a general star, with typical evolutional process of birth, development and death.

Heraclitus’ view has a great importance also by a psychological perspective. We are all aware of the continuous transformation of reality. Also our cells, our thoughts, our ego, everything is evolving. It looks like trivial, but if I consider all the changes in my life with respect to my childhood, I realize that a lot of people disappeared, new people appeared, the grandparents are not anymore in my horizon, but now I have kids and there are nephews. I have changed ideas, trends, opinions, body, aspect. Reality does change and according to Heraclitus it is the result of a perpetual fight of contrasting forces. It is an eternal becoming. We need to accept it.

Heraclitus is thus stating no trivial consideration, but by extrapolating his observation he identifies a universal cosmological principle that is valid till today. Reality is becoming.

During the same years a contemporary philosopher started a controversy with Heraclitus’ view, presenting a completely different approach: Parmenides of Elea. A long time earlier than Heraclitus, the school of Miletus, with its famous philosophers Thales, Anaximenes, Anaximander, had been investigating the nature in search of a principle (ἀρχή) of everything, a substance as foundation of the world beyond appearance (sub-stance, this means what under – stays everything, in Greek ὑποκείμενον), a steady cause against the continuous apparent changing of things. Thales proposed that water is not only the substance of seas, ice and vapors, but that is the substance of the whole universe. In other words that everything was made of water.

In a similar way, Parmenides accepted a unique principle, in opposition to the multiplicity of fighting principles of Heraclitus, but also in opposition with Pythagoras’ school that was proposing a principle based on the plurality of numbers. The unique Parmenides’ principle is not a substance identified by the observation of natural phenomena, but it is derived by a mental, logical deduction. We observe a great diversity in the world, but every observed object share a common characteristic: IT IS. This means it exists, and it can be thought of. An apple “is”. A table “is”. A cloud “is”. The common characteristic is that every object is, exists, can be thought of.

Parmenides thus is the first philosopher to investigate the “being”, or the “ontology” (from τὸ ὄν, “that which is” or “being”), the study of the characteristic of “being” as “being”. With him, philosophy makes a huge step toward the abstraction. The philosophical method of Parmenides is completely new. First of all he logically defines the word “being” and then he applies the deductive method (using a lot of reductio ad absurdum) to gain new conclusions. The conclusions can contradict the empirical experience. Using the deductive method, he clearly separates the logic of “being” from the logic of “not-being”, meaning that something either is or is not, without a possible halfway. The philosopher can express the characteristics of the “being”: the being is unchanging, motionless, indivisible and unique.

For the sake of example on the type of logical reasoning applied by the philosopher, we can meditate whether the being is changing or unchanging. Let’s imagine that the being is changing. This mean that in this moment the being is what it was not before, and before it was something that now it is not. If it were so, the being would have both the characteristics of being and of not-being, violating the complete separation of the being against not-being logic. This would be and absurd (reductio ad absurdum), therefore the being is unchanging.

Logic thus is more important than senses to grasp the truth of the world. Senses do not show the reality of the universe, but just provide means to get an opinion (δόξα), generally an illusory one. The changing of the world is an illusion, like the limit of our lives and the death itself. The truth lies within the eternity of the being, not in the illusion of the changing.

This approach is not far away from the Buddhist teaching, so we can say that today there are millions of people that would see this statement as a correct one.

Plato, between the 5th and the 4th century BCE, is facing a critical situation, seeing from one side the Heraclitus’ philosophy of the pure changing, a kind of philosophy of chaos, and from the other side the Parmenides’ approach that denounce the perceptible world as fake, a worthless illusion.

Plato finds the solution proceeding step by step, by confuting an opinion of the sophists that were asserting that the search for knowledge is impossible because:

- If you already know the object you are investigating on, the search would be fruitless;

- If you don’t know the object you are investigating on, you cannot recognize it even if you find it, therefore the search would be fruitless either.

Plato rejects this argument with the theory of the anamnesis. He accepts the doctrine of the immortality and reincarnation of the souls (metempsychosis), from the Orphic religion and Pythagorean philosophy, and he affirms that the objects have been already known by the immortal soul before the birth, while the subject, during his life, recognizes the “forgotten” objects by remembering them in the depth of his soul.

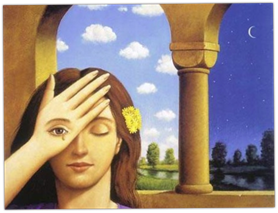

The debate is gnoseological, related to the knowledge, but has important consequences also in ontology. In fact, in the cognitive process, our soul let us remember forms (or ideas) that are incorruptible, eternal, unchanging, this means much closer to the Parmenides’ being than to the perceptible phenomena. These forms are absolute truth, absolute good, absolute beauty. How did our soul happen to learn the forms?

When our soul is free from the weight of the body, before incarnating, flies over the celestial sphere, in the hyper-uranium (that means “over the sky”), where the forms abode. Once the soul is incarnated, she is prisoner of the perceptible body, but she remembers the forms and has, in this way, a spelling book for knowledge. If I see a tree (one in particular, the one under my window, tall and green a little bended toward east), the anamnesis let me identify it as a tree, as I remember the general form of the tree in my mind.

Forms are not only a spelling book for souls, but they are the basis of the world. The perceptible world is not just an illusion, but it is the reflection, in temporary and imperfect way, of the eternal perfection of forms, and it is for us an incentive to remember the forms, stored in our memory, in our soul. Perceptible world let us build up an imperfect knowledge based on the memory of forms, that are reachable in the hyper-uranium.

In other words, Plato combines and harmonizes the philosophies of Heraclitus and Parmenides when he affirms (like Heraclitus) that in the physical world there is no a single principle as thought by the Milesian school, but it is ever changing; however the phenomenological reality is a reflection of eternal pre-existing forms. Matter does not become a cat by chance, but has to follow a pre-established cat-pattern, the perfect form in the spiritual world of the being.

In this way the multiplicity of the phenomena of the material world is not just an illusion, but it is somehow derived from the forms in the being. What we see in the material world are many imperfect imitations of the perfect forms. The latter cannot be seen by eyes or felt by perceptions, however can be glimpsed by the intellect.

Plato starts the verticality that we shall meet later in Neoplatonism, with matter in the inferior level and the forms in the upper level, the one of the being, with a dense relation between the two worlds.

In the next chapter we shall investigate more aspects of the innovative Plato’s thought.

Mario Basile